-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Unmana Sarangi*

Corresponding Author: Unmana Sarangi, Director, IES, Ministry of Environment Forest & Climate Change, Government of India, New Delhi – 110003, India.

Received: August 12, 2025 ; Revised: September 18, 2025 ; Accepted: September 21, 2025 ; Available Online: September 26, 2025

Citation:

Copyrights:

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

The research paper entitled “Carbon Pricing and Fiscal Sustainability in Asia Pacific Region” is basically a study of the carbon markets, carbon pricing mechanism, ETS, carbon taxation and pricing policies, linkages between cross border carbon mechanism with the national ETS mechanisms and the fiscal policy and sustainability stance on carbon pricing that has been adopted across countries in the Asia Pacific region.

The Asia Pacific economies and the EMDEs of the region face serious multiple challenges with respect to climate change and the adoption of the carbon pricing mechanism. Though the challenges concerning climate change is a burgeoning problem in the region, the Asia Pacific region has also been reeling under the vagaries of natural disasters such as earthquakes, foods, tsunamis, cyclones, disaster risks and the food-climate-finance-poverty nexus including the global poly crisis. Despite the above challenges, the Asia Pacific economies have the potentiality to tackle the issue of climate change through adoption of well-designed climate adaptation and mitigation policies as reflected in their NDCs, which these countries have submitted to the UNFCCC under the Paris Agreement. The NDCs are also being updated by the countries concerned in the region from time to time. It is a well-known fact that the region has adopted a well-developed and robust carbon pricing mechanism by considering the national priorities, national circumstances and the different levels of economic development of the region. The small island countries such as the Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, Samoa etc., in the Asia Pacific region are more prone to the natural disasters, which make it difficult for these SIDS to develop a definite carbon pricing mechanism. It is understood that carbon pricing has a strong linkage with the emissions trading systems developed by these economies in the region, which is backed by a well-developed fiscal sustainability policy pertaining to carbon pricing. Hence, it is felt that carbon pricing and the fiscal sustainability variables are complementary to each other. The ETS adopted in the region should consider the fiscal policies, regulations and structures of the Asia Pacific. The aspects dealt in the study include adoption of carbon pricing mechanisms, ETS, regulatory policies, rules and structures with respect to carbon market mechanism, trends in global carbon markets, need for a unified carbon market rule/mechanism in place, types of carbon markets in the Asia Pacific region, border adjustment mechanisms, carbon pricing in the macroeconomic context, cross-border carbon adjustment mechanisms and its implications in the Asia Pacific region, regulated power markets and emissions trading systems in the region, relationship between carbon taxation and carbon pricing policies, linkages between national ETS and cross-border carbon adjustment mechanism, fiscal sustainability and climate change and role of IMF in achieving fiscal sustainability in the Asia Pacific region.

A research methodology has been devised and developed given the availability of macro data on parameters such as carbon market, carbon pricing, emissions trading systems, market rules, regulations and structures, types of carbon market mechanisms, carbon pricing across borders, internationally transferred mitigation outcomes, GHG emissions, regulated power markets etc., Though the data/information are available, but country specific data/information on these macro parameters in a continuous time series pattern is difficult to fetch as the same are not available in a single source of data directory so that the data on these parameters become comparable to analyze the same statistically by using sophisticated econometric tools and methodology. Needless to add, it is a herculean task. For example, the data/information provided for the Asia Pacific region as declared by the countries in their respective NDCs also differ w.r.t. to type of information and the time lines of implementation with respect to adopting and achieving sector-specific targets and economy-wide measures in the region in the long-run. This distorts the very purpose of data collection, collation, analysis and in arriving at meaningful policy recommendations and conclusions for the Asia Pacific region with respect to adoption of these measures. For example, secondary data/information are available from international organizations and published sources such as United Nations, IPCC, UNESCAP, UNEP, ADB, World Bank, IMF, International Carbon Market Institute, Melbourne, Australia, PWC, OECD etc.

The policy recommendations and conclusions have been drawn out from the study, which entail that for preparation for market linkage, nations should focus on understanding and addressing their domestic carbon market dynamics, establishing a communication platform or leveraging the capabilities of international organizations can facilitate policy sharing and coordination, implementing a legal MRV (Measurement Reporting and Verification) framework for compliance tracking is crucial for ensuring that emission reductions are accurately measured and reported, creating an international carbon allowance calculator enables fairness in calculating international carbon footprints and monetary cost flows, implementing cooperative policies to ensure the environmental integrity of linked carbon markets is essential, strengthening financial regulations and policies is crucial to mitigate potential risks associated with carbon finance, including fraud, misleading information, manipulation, and transfer pricing.

Keywords: ETS, Carbon Pricing Mechanism, CBAM, ITMOs, Unilateral Transfers, Fiscal Sustainability

INTRODUCTION

The Asia Pacific economies and the EMDEs of the region face serious multiple challenges with respect to climate change and the adoption of the carbon pricing mechanism. Though the challenges concerning climate change is a burgeoning problem in the region, the Asia Pacific region has also been reeling under the vagaries of natural disasters such as earthquakes, foods, tsunamis, cyclones, disaster risks and the food-climate-finance-poverty nexus including the global poly crisis. Despite the above challenges, the Asia Pacific economies have the potentiality to tackle the issue of climate change through adoption of well-designed climate adaptation and mitigation policies as reflected in their NDCs, which these countries have submitted to the UNFCCC under the Paris Agreement. The NDCs are also being updated by the countries concerned in the region from time to time. In fact, it is learnt that the region has adopted a well-developed and robust carbon pricing mechanism by considering the national priorities, national circumstances and the different levels of economic development of the region. The small island countries such as the Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, Samoa etc., in the Asia Pacific region are more prone to the natural disasters, which make it difficult for these SIDS to develop a definite carbon pricing mechanism. It is a well-known fact that carbon pricing has a strong linkage with the emissions trading systems developed by these economies in the region, which is backed by a well-developed fiscal sustainability policy. Hence, it is felt that carbon pricing and the fiscal sustainability variables are complementary to each other. The ETS adopted in the region should consider the fiscal policies and regulations of the Asia Pacific. The aspects dealt in the study include adoption of carbon pricing mechanisms, ETS, regulatory policies, rules and structures with respect to carbon market mechanism among other aspects.

CARBON PRICING MECHANISM IN ASIA PACIFIC: A WAY FORWARD

There are deliberations in the international fora that climate goals need to be pursued by adopting a low-carbon economy across economies and sectors including the Asia Pacific region. Hence, transitioning toward a low-carbon economy is required across countries and sectors by adopting a systemic change, through an array of climate policy instruments that incentivize change in behavior and bring about the investment and innovation necessary to shift economies toward the 1.5-degree pathway, as per the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. Hence, the role of carbon pricing mechanisms assumes paramount importance globally through operation within this broader climate policy architecture that include regulations, standards and certifications, technological innovations, and climate finance. At the same time, carbon-pricing mechanisms are also part of the broader context of national economic, energy and environmental policies, which also need to be aligned to effectively bring down GHG emissions across economies including the Asia Pacific region.

The development of the global carbon market has received widespread attention globally including the Asia Pacific. Carbon Forward Asia Meet held during March 7-8 2024 in Singapore gathered industry experts and scholars to discuss the current market situation and future trends. Participants from Singapore, Malaysia, China, South Korea, and the EU focused on two major topics i.e. the development of carbon markets in the Asia- Pacific region and the future of the global voluntary carbon market.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

A detailed review of literature has been undertaken in the research study by consulting research studies of various international organizations such as the United Nations, IPCC, UNESCAP, UNEP, International Carbon Market Institute, Melbourne, Australia, PWC, OECD, international multilateral financial institutions such as the ADB, World Bank, IMF, research papers of various research scholars, Policy Brief and Background Papers of ADB, World Bank etc., The detailed references are reflected below: [1-26].

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The topic of research is relevant in the present context the world is facing. It is understood that the world is reeling under the climate crisis including the countries that form the Asia Pacific region. The research broadly focuses on the aspects and linkages between carbon pricing, ETS and fiscal sustainability in the light of the recent international developments and in the context of the national economies of the Asia Pacific region. The Asia Pacific region suffers from not only the burgeoning climate crisis, but also the vagaries and hazards of natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunami, floods, cyclones, extreme weather conditions that are specific to the region, which it is encountering. Hence, studying carbon pricing, carbon markets and the ETS of the Asia Pacific region including its fiscal implications, sustainability and the related rules, regulations and framework is apt in the present-day context of the global climate goals and the related NDCs that are being implemented across various regions of the world as per the instance of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. In view of the above, the following research questions are pertinent in the context of the Asia Pacific region viz;

The detailed answers to these questions are highlighted below:

DIVERGENCE IN SOUTH EAST ASIA’S CARBON PRICING SYSTEMS

Globally, the carbon market in the Asia-Pacific region is gradually maturing, but the carbon-related mechanisms in Southeast Asia remain quite fragmented. Unlike the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), Southeast Asia has developed its own rules and regulations & standards for adopting carbon-pricing mechanism. Reviewing Southeast Asia's carbon pricing mechanisms reveal that each country in the region adopts slightly different strategies. Indonesia, as one of the world's top ten greenhouse gas emitters, is the first country in the region to establish an ETS. Compared to government-led mandatory carbon markets, voluntary carbon markets, primarily focusing on carbon offsetting, are favored by many Southeast Asian countries. For example, Malaysia's Bursa Carbon Exchange and Thailand's FTIX Carbon Trading Platform started operations during 2023. Additionally, Singapore's carbon tax system and carbon credit trading are more mature, with comprehensive regulations and market liquidity.

DIFFERENTIATED STRATEGIES FOR SOUTHEAST ASIA’S CARBON MARKET

The Southeast Asian countries choose different market systems compared to the EU ETS, implemented since 2005. The development of voluntary carbon trading markets is a primary strategy. There are three main reasons behind this choice viz; differences in political systems, energy structures and levels of economic development.

DIFFERENCES IN POLITICAL SYSTEMS

Compared to the highly integrated EU, Southeast Asia has significant differences in policies and regulations, making it difficult to establish a unified carbon market. Furthermore, the EU has demonstrated high political will and leadership towards common emission reduction goals, while Southeast Asian countries have yet to achieve such political consistency, consensus and cooperation in this regard. Therefore, diverse carbon market models are more effective in these regions.

DIFFERENCES IN ENERGY STRUCTURES AND EMISSION SOURCES IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN COUNTRIES

The energy structures and emission sources in Southeast Asian countries vary across sectors. Some countries rely more on fossil fuels, while others focus more on renewable energy development based on the different levels of the countries in the region. For instance, Indonesia primarily uses coal to meet its energy needs, while Vietnam has significant potential in solar and wind energy. These differences greatly influence the strategies each country adopts for their carbon markets. As a result, the carbon market scenario at the global level and its determination would be quite different in the Asia Pacific context.

DIFFERENCES IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Southeast Asian countries have varying levels of economic development and industrialization. Implementing mandatory carbon markets could significantly impact their economies. Developing voluntary carbon markets offers a flexible and liquid mechanism, allowing companies to choose whether to participate, thus incentivizing carbon trading behaviors and promoting market development.

In one of the conferences, World Bank financing expert Jeffrey Delmon acknowledged Southeast Asia's strategy for voluntary carbon markets. Establishing a cooperative carbon market system is crucial. For example, Singapore has bilateral agreements with Indonesia and Bhutan for carbon credit transfers, and Vietnam has extended its market to the Asia-Pacific region, becoming the fourth-largest carbon project issuer under Japan’s JCM mechanism. As countries gradually introduce carbon-pricing systems, whether Southeast Asian carbon markets can be integrated is a moot question and will be a focal point.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

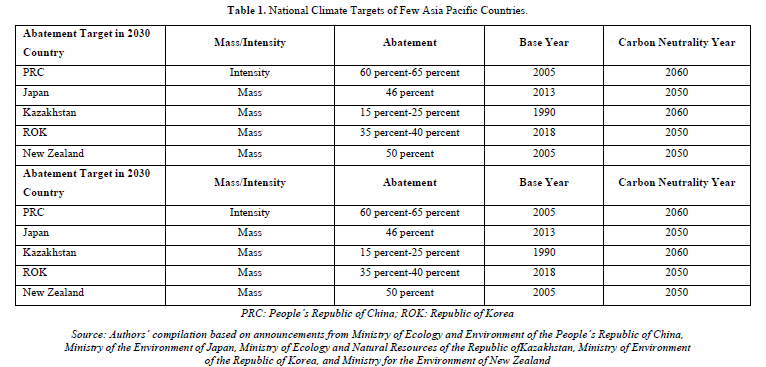

A research methodology has been devised and developed given the availability of macro data on parameters such as carbon market, carbon pricing, emissions trading systems, market rules, regulations and structures, types of carbon market mechanisms, carbon pricing across borders, internationally transferred mitigation outcomes, GHG emissions, regulated power markets etc. Though the data/information is available, but county specific data/information on these macro parameters in a continuous time series pattern is difficult to fetch as the same are not available in a single source of data directory so that the data on these parameters become comparable to analyze the same statistically by using sophisticated econometric tools and methodology. Needless to add, it is a herculean task. For example, the data/information provided for the Asia Pacific region as declared by the countries in their respective NDCs also differ w.r.t. to type of information and the time lines of implementation with respect to adopting and achieving sector-specific targets and economy-wide measures in the long-run. This distorts the very purpose of data collection, collation, analysis and in arriving at meaningful policy recommendations and conclusions for the Asia Pacific region with respect to adoption of these measures. For example, secondary data/information are available from international organizations and published sources such as United Nations, IPCC, UNESCAP, UNEP, ADB, World Bank, IMF, International Carbon Market Institute, Melbourne, Australia, PWC, OECD etc., The table below provide the data/information on NDCs of the Asia-Pacific countries as per the requirement of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement (Table 1).

The above table reflects the data/information on national climate targets of few Asia Pacific countries. From the data/information, it can be inferred that the macro parameters such as abatement target of countries, mass/intensity and the carbon neutrality component are not comparable across the entire region amongst various countries as the base years are different for different countries. It is observed that the countries in the Asia Pacific region adopt different timelines of implementation of their NDCs on account of their national circumstances, priorities and levels of economic development. These countries update their NDCs on a regular basis from time to time and report the same to the UNFCCC as per the Paris Agreement. The percentage of abatement across sectors also are different for countries in the region including that of the carbon neutrality targets set by these countries. This could also account to factors such as adoption of different carbon pricing mechanisms, ETS, rules, regulations and structures including fiscal policies and sustainability in the region in the long-run.

Major Trends in the Global Carbon Market and Measures required for Achievement of Robust Carbon Pricing Mechanism

The quality of carbon credits has garnered attention after several carbon credit controversies. Factors like methodology recognition, regulatory measures, carbon credit issuance and certification are standards for quality determination. However, there is still a lack of uniformity in the international carbon credit market, and the complexity of market systems deters investors. There are significant issues to watch in the global carbon trading market. In order to achieve proper and robust carbon pricing mechanisms the following are required:

NEED FOR UNIFIED MARKET RULES

Despite the growing influence of voluntary carbon markets globally, differing market systems remain a challenge. Different regions have varying understanding, rules and enforcement methods for carbon markets complicating market participation. Establishing consistent market rules and standards provides a guideline for companies and promotes market activity. The global carbon market requires more regulations to collectively achieve global climate commitments. As the impact of the carbon market grows, companies will play a more crucial role in emission reductions. Considering the different development systems of carbon markets in various regions, early planning can seize market opportunities and address challenges arising from market changes.

TYPES OF CARBON MARKETS MECHANISMS

Mandatory or compulsory carbon markets are known by many names viz; (i) cap and trade programmes, (ii) emission trading schemes (ETS) and compliance markets. In this case, the government (i) sets a cap on emissions in certain sectors, usually on sectors with the highest emissions; (ii) issues equivalent allowances by allocating these two firms for free or for a fee; (iii) let’s firms trade the allowances among themselves by allocating among themselves. Large emitters that face high costs in lowering emissions may choose to buy allowances from other firms, while low-cost firms have incentives to invest in reducing emissions since they can sell unused allowances in carbon markets. On the other hand, voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) trade voluntary carbon credits (VCCs). Governments and businesses earn carbon credits when they invest in projects that reduce GHG emissions compared to a baseline scenario, which they can then trade. VCCs are typically used by companies to offset GHGs emissions and achieve their carbon neutrality goals. International Climate Agreements have also paved the way for countries to use VCCs to meet their NDCs targets. Hence, the Asia Pacific region can emulate and replicate the said strategy in their countries.

COUNTRY CASE STUDIES IN ASIA PACIFIC

Across Asia, there is a growing momentum in the application of carbon pricing instruments. Examples are carbon taxes in Japan and Singapore, ETS in the PRC, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and New Zealand. Local context and circumstances are a key factor in the design and application of these instruments, and includes national commitments to reducing GHG emissions and considerations of economic and distributional impacts. The three country case studies that are reflected below illustrate the interplay between general design principles and local conditions that are unique to each. The different stages of implementation further demonstrate the considerations at various stages of development.

THAILAND DESIGNING CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS

Thailand aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and net zero GHG emissions by 2065. The country’s climate strategy relies on decarbonization of the energy sector and promotion of a green economy, with residual emissions absorbed through the forestry sector. In the past, Thailand has mostly used positive incentives to encourage investments in green projects, including the use of the VCM and voluntary trading under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. However, in the design of carbon pricing mechanisms, the intention is to use economic instruments to motivate divestments from GHG-intensive activities in a way that is aligned with a just transition and is conducive to sustainable economic growth. Thailand aims to employ both a carbon tax and a carbon market, in phases, by 2030. A broad-based carbon tax on fossil fuels will be implemented first, while the necessary infrastructure to operate the ETS is established. The plan is to require big emitters to report their GHG emissions, then apply cap-and-trade to some of these emitters. In the final implementation phase, ETS allowances will be auctioned with proceeds going into the Climate Change Fund (CCF). This fund will support mitigation measures and investments in adaptation, paving the way for a just transition. Going forward, Thailand must establish the necessary infrastructure including a monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) system, ensure the alignment of carbon pricing policies with other environmental and energy policies, alleviate competitiveness concerns and engage with relevant stakeholders in this direction.

JAPAN: INITIAL STAGE OF GREEN TRANSFORMATION

Carbon pricing is part of Japan’s broader green transformation or so-called GX strategy that aims to foster low-carbon economic growth by stimulating private and public investments in green technology and incentivizing decarbonization in industries. In addition to carbon pricing, the GX strategy includes public climate finance to support green investment (i.e. issuing Yen 20 trillion in GX Economy Transition Bonds for a period of 10 years) and transition finance through public-private partnerships. The goal is to achieve Yen 150 million of public and private investments to realize a green transformation, transition away from a fossil fuel-oriented economic and industrial structure and bring about a clean energy-oriented economy. Japan aims to achieve a 46 percent reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050. Japan’s ETS (GX-ETS) has been operational since April 2023. The first phase is voluntary and steered by the GX League, which is composed of companies that are responsible for half of the country’s GHG emissions. Phase 2 from 2026 onward will be the full-scale launch of the ETS, and membership will be gradually expanded along with putting in place the necessary targets and infrastructure for fully operationalizing a cap-and-trade system. In Phase 3, GX-ETS will be further developed to encompass the auctioning of allowances for power generation utilities. The key challenge in rolling out the system is ensuring price stability while leaving room for market mechanisms to work. Japan also plans to impose market mechanisms to work. Japan also plans to impose carbon surcharges on fossil fuels by 2028.

KAZAKHSTAN: EARLY ADOPTER OF ETS

Kazakhstan’s primary carbon pricing instrument is the ETS that was launched in 2013. The ETS covers carbon dioxide emissions from large enterprises in the energy sector, and in industries such as oil and gas, mining, metallurgy, chemical and manufacturing. This translates to 41.1 percent of the country’s emissions. National allocation plans specify the distribution of allowances. In the current operation of Kazakhstan’s ETS, the country has transitioned away from allocating allowances based on historical emissions to product-based benchmarking [17]. Prior to its launch, the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources established the ETS regulatory framework, which is aimed at the facility level. Regulated facilities are required to submit reports to relevant government authorities, which are then verified by accredited third parties. Trading occurs in the secondary market only and mainly through the commodity exchange, with a small proportion of allowances traded directly between companies. As an early adopter of the ETS, Kazakhstan faced operational issues associated with running a cap-and-trade system, which led to the suspension of the carbon market in 2016-17. The market resumed operations in 2018 following legislative changes in the overall GHG emissions regulation, ETS operation, and MRV system, and to lay the groundwork for introducing benchmarking in the allowance distribution. Kazakhstan hopes to further improve its ETS by (i) putting in place measures to ensure accuracy of emissions reporting and integrity of the MRV process, (ii) imposing stricter benchmarks of existing products and (iii) expanding carbon pricing to other sectors either through ETS or through carbon taxes. Kazakhstan also plans to introduce auctioning of carbon allowances and to align its system with international carbon markets such as the EU-ETS.

CARBON PRICING ACROSS BORDERS

While the application of carbon pricing instruments will primarily be at the domestic level in Asia, countries should keep in mind the global trend of increasing internationalization of climate policy instruments. International collaboration has always been promoted to help bring down the cost of reducing GHG emissions. One example is the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol which serves as a precursor to Japan’s JCM. These interactions between countries and markets are set to increase with the adoption of the Paris Agreement and rules on the international transfer of carbon credits, the proliferation of voluntary and mandatory carbon pricing mechanisms, and the growing recognition that international trade should also account for GHG emissions of traded goods. The existence of multiple carbon pricing mechanisms and emerging application of carbon prices in several countries lead to carbon price differentials. Higher prices impact carbon-intensive industries, putting domestic firms at a competitive disadvantage compared with foreign firms and leading firms to relocate to areas with lower prices or to regions that do not yet have carbon pricing regulations. This leads to leakage, which undermines the effectiveness of domestic climate policies. Border adjustment mechanisms act as import taxes on the GHG content of goods and can be used to prevent this leakage.

Countries should consider the following points in designing carbon-pricing strategies.

INTERNATIONALLY TRANSFERRED MITIGATION OUTCOMES (ITMOS)

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement allows for countries to engage in cooperative approaches to reduce GHG emissions generating Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes. Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs), the term used for carbon credits that can be transferred between countries and used to meet a country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). This can stimulate investments in projects that reduce GHG emissions in developing countries. One case in point is the ITMO transaction between Thailand and Switzerland where the latter makes green investments in the former in exchange for ITMOs. Other countries pursuing similar bilateral agreements with host countries are the ROK, Singapore, and Sweden (Kerschner and York 2023). Apart from ITMO transactions, the private sector also engages in the international sale of carbon credits through VCMs. With increasing corporate commitments to achieving net zero, these transactions are set to increase. With the right preparations, developing Asia can capture the benefits of these developments.

CARBON PRICING IN THE MACROECONOMIC CONTEXT

Carbon pricing helps internalize the external costs of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by incorporating a cost of carbon into production and consumption decisions. This cost of carbon could, in principle, represent the abatement cost needed to meet a mitigation goal, or represent the societal cost associated with the GHG emissions arising. There is a broad landscape of carbon pricing instruments which ranges from direct to indirect ways of pricing carbon. Among the direct ways of pricing carbon, carbon taxes, and emission trading system (ETS) are the two most common instruments. Baseline and crediting systems, such as international carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, can also put a direct price on carbon. On the other hand, fossil fuel taxes and, in some cases results-based finance, can price carbon indirectly.

CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR DEVELOPING ASIA VIS-A-VIS EUROPEAN COUNTERPARTS

Carbon pricing is an integral element of the broader climate policy architecture that can be used to reduce emissions and achieve nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets cost- effectively while generating revenue and incentivizing the deployment of low-carbon technologies. Despite the challenging macroeconomic context, there is a growing momentum to utilizing carbon pricing instruments, including carbon tax, emissions trading system (ETS) and international carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. There has also been a rising interest in cross-border mechanisms such as border carbon adjustments to address carbon leakage. The development of carbon pricing is in the rise in Asia as well, but the region faces unique circumstances. Key challenges and policy solutions include: (i) prevalence of regulated power markets, which requires looking at coverage of indirect emissions, climate oriented or green dispatch, establishing pricing committees and introducing consumption charges; (ii) potential distributional impacts, which requires safeguarding business and consumers by introducing tax discounts, exemptions or rebates; and (iii) lack of institutional capacity and policy coordination, which requires significant capacity building support. Recognizing these unique and regional circumstances, developing Asia can continue in its growing momentum to utilizing carbon pricing instruments as a key tool to enhance climate action and ambition.

There is a growing momentum to utilize carbon pricing instruments not just globally but also in developing Asia with seven instruments emerging and/or implemented in the national level. In addition, with the finalization of the Paris Agreement Rulebook, there is a growing momentum on operationalizing international carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Cross-border carbon pricing mechanisms to address carbon leakage, such as through European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, are also emerging.

The global development of carbon pricing has implications for developing Asia. For developing Asia, it will be important to consider carbon pricing taking account of national circumstances and select an instrument, or instruments, that fit the regulatory and market tradition in the country. Addressing barriers to carbon pricing adoption will be key, and three challenges are pertinent:

A two-pronged approach is therefore needed in developing Asia. First, where possible, these barriers should be removed. Second, carbon pricing should be designed to be most effective where these challenges remain. This includes ideas around covering indirect emissions and consumption charges to adjust to regulated power markets, providing rebates to address distributional impacts, promote knowledge transfer and capacity building. The issue of energy subsidies in developing Asia will be especially sensitive, as the removal of these to create an environment conducive to carbon pricing would itself raise concerns about the ability of consumers to pay elevated energy costs.

The PRC’s national ETS is noteworthy as it was launched in February 2021, becoming the world’s largest carbon market. Initially covering around 2,225 entities in the power generation industry, the ETS regulates annual emissions of around 4,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide (MtCO2). Regulated entities had to surrender allowances to cover their 2019 and 2020 emissions in 2021. Penalties for the national ETS are being drafted currently by the State Council, with interim regulations proposing fines for entities that fail to surrender sufficient allowances by the compliance deadline. The ETS in PRC includes free allocation based on benchmarks and a mix of carbon emissions intensity and actual production, which is sort of output-based free allocation. As a result, this CO2 emissions reductions during 2020-2030, mainly result from shift from less to more efficient unabated coal-fired technologies.

Indonesia is the latest country in the region to move forward with carbon pricing adoption by pursuing a hybrid "cap-trade-and-tax" instrument. Indonesia has considerably improved its tax system over the past decade in respect to both revenues raised and administrative efficiency. Following the objectives of Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contributions and the issuance of Government Regulation No 46/2017 on Environmental-Economic Instruments which states that the emissions trading system is to be implemented no later than 7 years since the regulation was established, the discussion/deliberations on carbon pricing issues has developed rapidly in Indonesia. In 2017, Indonesia engaged in international cooperation through the Partnership for Market Readiness. Several technical assistance projects and studies on greenhouse gas monitoring and reporting and carbon pricing instruments design were conducted. Alongside countries that have already introduced or are implementing carbon pricing, there are countries that are thinking about introducing carbon pricing instruments. Viet Nam is making significant progress in introducing a carbon price in their jurisdiction, and according to the International Carbon Action Partnership, Pakistan; the Philippines; Taipei, China and Thailand also currently are considering adopting a domestic ETS. In addition, Brunei Darussalam has identified carbon pricing as one of the country’s key strategies for driving the transition toward achieving a low-carbon economy in the 2020 Brunei Darussalam National Climate Change Policy. Meanwhile, India has launched its carbon trading platform in August 2022 paving the way for a national carbon market in the country.

Outside of carbon taxes and ETS, there is also a growing momentum in operationalizing international carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. This is particularly relevant for Asia and the Pacific as it has a wealth of experience and expertise in operationalizing international carbon markets as approximately 80 percent of all Clean Development Mechanism projects are hosted in the region. This experience and expertise are also relevant to international carbon markets under the Paris Agreement. In addition, the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) is a forerunner to Article 6.2, and about 90 percent of all JCM projects are hosted in the region.

Although the fundamental design and theory of carbon pricing are similar in countries globally, practices in Asia and the Pacific differ from those in other parts of the world in various respects, particularly in the context of choice of instrument and approach in implementation. A comparison with Latin America, for example, is an interesting one given that climate enthusiasm and ambition are increasing in both regions, as are successes in clean energy and biodiversity protection efforts. As of March 2021, the Latin America region had in place one ETS (Mexico); four federal carbon taxes (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico); and three sub-national carbon taxes in Mexican states. Aside from the carbon tax with offsets component that is already in place, Colombia's ETS is in the works. Brazil and Chile are investigating ETS development, whereas Costa Rica is involved in JCM operations.

Carbon pricing mechanisms in Asia’s developing countries (middle-income) have not introduced fuel excises, i.e., indirect carbon taxes, while this was the case for several countries in Latin America. Such taxes may not have a large impact on emissions but provide regular revenue to the government budget. One trend is that countries such as Argentina, Colombia and Mexico start their way into preparations for ETS with existing indirect carbon taxes in place. While initially incorporated into larger tax reforms, all carbon taxes in Latin America achieve different and context-specific policy objectives, such as environmental tax. Asian countries usually seem to allocate revenues for emission reduction and low-carbon projects and support. Singapore for example, uses carbon tax money to fund projects that reduce GHG emissions.

CARBON BORDER ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM (CBAM): IMPLICATIONS FOR ASIA PACIFIC REGION

The Asia and Pacific region have a relatively low risk of exposure and vulnerability to CBAM because trade with the EU is a relatively small proportion of the region’s overall trade portfolio. The countries from Asia and the Pacific most impacted by EU-CBAM are the PRC, Japan, the ROK and India which are among the top 10 largest economies in the region and make up 4 of the top 10 import partners for the EU. Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Thailand and Viet Nam are also impacted because of their overall trade volumes with the EU. It is important to note that PRC, Japan, and the ROK all have domestic carbon pricing instruments which may cushion the potential impacts of EU-CBAM as long as the sectors being exported to EU are covered under the domestic carbon price as well as in EU’s list of high emission sectors within the scope of EU-CBAM. However, given the significant differences in price of carbon between the jurisdictions, a price will have to be paid at the border unless price levels meet the ones within the EU. This is the bedrock of a BCA as it iterates the importance of a common price on carbon globally. In view of the above, EU-CBAM is a unilateral measure being adopted when compared with the Asia Pacific economies as these economies are the major importers of the EU.

REGULATED POWER MARKETS AND EMISSIONS TRADING IN ASIA PACIFIC

The power sector is included in virtually all operating ETS for four main reasons. First, it is because of the power sector being a major source of GHG emissions with coal-fired electricity generation alone accounting for 30 percent of global CO2 emissions. Second, abatement costs in the power sector are generally cheaper compared to other sectors. Third, a low-carbon power sector will play a key role in decarbonizing the heat and transport sectors. Fourth, the sector typically consists of relatively few large fossil-based emitters, with clear installation boundaries and simple monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) processes.

Whereas the four reasons for including the power sector are good arguments for including the power sector in ETSs in Asia and the Pacific, the way the power sector typically is governed and organized in the region could be a challenge for implementing ETSs in the region. Emissions trading works best in deregulated power markets since generation, supply, and networks are unbundled, electricity is traded in wholesale markets, generators have free access to the market, independent regulators are assigned to monitor the market, and customers are free to choose their electricity supplier.

The cost of an ETS allowance or a carbon tax creates various levels of incentives for the power sector to reduce emissions, for example by investing in less carbon-intensive power supply, reducing electricity demand or changing the merit order of electricity dispatch in favor of low-carbon power supply. In practice, however, power markets are often fully or partially regulated, and some power market structures can weaken or hinder the carbon pricing signal, reducing the instrument’s effectiveness. It is essential for the design of a carbon pricing instrument to match local circumstances to generate the most effective carbon price signals.

CHALLENGES IN CARBON PRICING IN ASIA PACIFIC AND POLICY OPTIONS

There are several options that can support countries address the challenges with lack of institutional capacity and policy coordination. First, engagement and timely coordination with development multilateral financial institutions such as the Asian Development Bank, can help identify avenues and opportunities for capacity building. Second, regional cooperation to facilitate knowledge transfer between countries that share similar circumstances and priorities can provide pathways for carbon pricing adoption relatable to the countries. To do all these, it would be important to establish inter-ministerial committees, given carbon pricing identification and implementation requires a host of ministries to be aligned in this region. In addition to seeking external support, it is important to ensure any significant capacity and institutional building exercise builds on the existing infrastructure and systems. For example, countries that are participating actively under the Joint Crediting Mechanism, a project-based offset crediting mechanism implemented by the government of Japan, can build-off the existing infrastructure and systems to operationalize international carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

For the Asian Development Bank’s member economies, it will be important to consider carbon pricing, considering national circumstances, and select an instrument, or choices of instruments, that fit the regulatory and market tradition in these economies/countries. Emphasis needs to be placed on understanding country and region-specific barriers that may hinder not just the introduction but the eventual implementation of carbon pricing instruments. As such, there needs to be action to remove these barriers and careful design of policy approaches, for which there is a need to understand not just global best practices in carbon pricing implementation but also unique circumstances and challenges in the country.

Momentum is growing for the use of carbon pricing in the Asia and Pacific region. Across the region, eight national carbon pricing initiatives had been implemented or are under implementation. Japan and Singapore both employ carbon taxes, while Australia, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), and New Zealand have all implemented a national ETS (Emission Trading System). Sub-national ETS are also employed by local jurisdictions in Japan, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are considering adopting a domestic ETS, while India is developing a domestic national carbon market. Momentum is also growing for economies in the region to take advantage of international carbon markets, through both emerging compliance markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the voluntary carbon market.

FOSSIL FUEL REFORMS IN ASIA PACIFIC: INDIAN AND INDONESIAN CONTEXT

India: Shifting Support from Fossil Fuels to Clean Energy

Since 2010, India has made noteworthy progress on fossil fuel subsidy reform through a calibrated “remove”, ‘target’ and ‘shift approach’. By carefully balancing the combined effect of three key policy levers i.e. retail prices, tax rates and subsidies on selected petroleum products the country was able to reduce its fiscal subsidy in the oil and gas sector by 85 percent, from an unsustainable peak of $25 billion in 2013 to $3.5 billion in 2023. India gradually phased out the subsidy on petrol and diesel (from 2010 to 2014) and carried out incremental tax increases (from 2010 to 2017), which created fiscal space to increase government support for renewable energy, electric vehicles and strengthening of electricity infrastructure. The additional tax revenues from increases in excise duty on petrol and diesel from 2014 to 2017, a period of low international crude oil prices, were also redirected to improve access and target subsidies for expanding the use of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) among the rural poor. Subsidies for LPG have since grown and may now require efforts to improve targeting and to incubate non-fossil-fuel cooking alternatives. From 2010 to 2017, the Government of India introduced a cess (tax) on coal production and imports. Around 30 percent of the cess collections were channeled to a national clean energy and environment fund that supported clean energy projects and research. The cess significantly contributed to strengthening the budget of India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy during 2010-2017 and provided the initial funds for the country’s Green Energy Corridor scheme and its National Solar Mission, which helped bring down the cost of utility-scale solar energy and fund many off-grids renewable energy solutions. However, with the introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) in India after 2017, the cess on coal production and imports was subsumed within the country’s GST compensation cess, the flows of which were redirected to compensate states for revenue losses associated with the new tax regime. As a result of India’s subsidy reforms and taxation measures, the country’s fossil fuel subsidies plummeted from 2014 to 2018. Its renewable energy subsidies also reached a peak in 2017 but are now once again growing, with major support schemes targeting solar parks, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and distributed renewable energy. These measures seem to be in alignment with adoption of fiscal sustainability for attaining effective carbon pricing mechanism in the said country.

Indonesia: Shifting Support from Fossil Fuels to Social Protection

Declining oil production and mounting subsidy bills when fossil fuel prices spiked led the Government of Indonesia to implement major reforms in 2005, 2008, 2013, and 2014. In 2014, Indonesia implemented measures to reform fossil fuel subsidies, taking advantage of falling world oil prices. These measures included the removal of all gasoline subsidies except for distribution costs outside the Java-Madura-Bali area. Price caps on diesel were replaced with a fixed subsidy, allowing diesel prices to fluctuate according to international prices but remaining Rp1,000 per liter below the market price. This policy resulted in a saving for the government of roughly $15.6 billion over 10 percent of Indonesia’s annual expenditure in 2015. Reforms need to be complemented by policies to protect vulnerable consumers. Policy reforms around fuel subsidies may not be politically viable unless they also address a wide array of social goals. Removing subsidies can sometimes cause hardship for vulnerable populations and businesses and below-market fossil fuel prices are often seen as part of the social contract in many energy-producing economies. Governments therefore need to identify vulnerable groups and businesses, anticipate impacts, and develop targeted assistance measures and compensation (such as cash transfers funded by subsidy savings) to address these impacts. In addition, some temporary financial support for the middle classes may also be needed to reduce the likelihood of political backlash. A commitment to reinvest subsidy savings in education, health, or cash transfers has been seen to double public support for subsidy reform. These measures seem to be in line with adoption of fiscal sustainability for attaining effective carbon pricing mechanism in the said country.

AGRICULTURE SUBSIDIES TO BE REPLACED BY CLIMATE-SMART INVESTMENTS

Subsidies for agriculture and land use drive emissions and environmental degradation. After the energy sector, agriculture and land-use change combine as the second-largest source of GHG emissions, accounting for a quarter of all emissions worldwide. Globally, agriculture subsidies reached a historical high of $851 billion per year for 2020-2022, a 2.5-fold increase from the levels of 2000-2002. The PRC and India accounted for 36 percent and 15 percent, respectively, of global agriculture subsidies in 2020-2022. About 74 percent of global agriculture subsidies go to producers in the form of market price support (such as import tariffs and other border measures) or payments for use of inputs (such as fertilizers and improved seeds). In parts of Asia, agriculture input subsidies have promoted such excessive overuse of fertilizers that yields have fallen and water pollution through increased nitrogen runoff has increased. Similarly, subsidies that lower the price of electricity, diesel, and water for irrigation have promoted overuse and led to methane emissions, especially from rice cultivation. Rice receives the highest share of subsidies among all commodities and is one of the top three sources of agriculture’s GHG emissions. In some economies of developing Asia, state concessions in forest areas have effectively subsidized deforestation and increased both emissions and environmental degradation [11].

Agriculture subsidies are poorly targeted and exacerbate existing inequalities. Most agriculture subsidies accrue to wealthier farmers, even when programs are designed to target the poor. Consumer subsidy programs usually require significant out-of-pocket expenditure by recipients, which discourages participation from lower-income households. Meanwhile, producer subsidies tend to scale with levels of production, which means a disproportionate share goes to larger producers.

Reforming and repurposing agriculture subsidies can help farmers adapt to climate change. A majority of agriculture subsidies are concentrated in market-distorting measures such as market price support and use of inputs, while the share of subsidies that support research and development, extension services, innovation, and infrastructure is small and declining. Investment in these areas has the potential not only to reduce emissions and environmental degradation but also to enhance the ability of farmers to adapt to the changing climate. Similar to the scenario with fossil fuels, agriculture subsidy reform should be based on a transparent process and multistakeholder consultation, with a clear communication strategy. It should also entail measures for those who face losses, such as cash transfers that target vulnerable people.

CARBON TAXATION AS A CORE CARBON PRICING POLICY

In Asia and the Pacific in 2024, only Japan and Singapore had implemented a national carbon tax. Japan began imposing a carbon tax in 2012, based on CO2 emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels across all sectors. Japan’s carbon price has been steady at ¥289 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) since 2016. However, the Government of Japan provides exemptions and refund measures for specific fossil fuels used in the agriculture, energy, industry, and transport sectors. Singapore started imposing a carbon tax in 2019, targeting facilities in the energy, manufacturing, waste, and water sectors that directly emit at least 25,000 tCO2e per year. Singapore has followed a phased approach to increasing carbon prices. Initially set at S$5 per tCO2e in 2019, the price increased to S$25 in 2024, and is set to increase further to S$45 by 2027 and to as much as S$80 by 2030. In Japan and Singapore, revenues collected from carbon taxes will fund government decarbonization efforts, including investments in low-carbon technologies and practices and implementation of energy efficiency measures. In Singapore, revenues will also be used to cushion the impact of the carbon tax on businesses and households. From 2024, companies use eligible international carbon credits to offset up to 5 percent of their taxable emissions. While carbon taxation is under consideration by more governments in the Asia and Pacific region, questions remain regarding policy design, macroeconomic implications, and impacts of a carbon tax on an economy’s international competitiveness. Taipei, China is set to imposing a carbon fee in 2024, which targets electricity and manufacturing facilities that emit more than 25,000 tCO2e of GHG. The government has not set the fee rate but has announced that preferential pricing will be provided to entities with approved emissions reduction plan.

EMISSIONS TRADING SYSTEM PRACTICES IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Of the 13 national ETSs established worldwide by 2024, six are in the Asia and Pacific region. National ETSs of various types operate in Australia, the PRC, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the ROK, and New Zealand. New Zealand’s ETS dates back to 2008 and is the second oldest in the world. It was followed by Kazakhstan and the ROK in 2013 and 2015, respectively. By 2016, the PRC had initiated pilot ETSs in eight cities and established a nationwide ETS in 2021. Australia does not have a formal ETS, but has operated a mandatory baseline-and-credit system since 2023. Indonesia’s ETS commenced in 2023.

The region’s six national ETSs differ in terms of their ambitions and implementation. All of them, however, are central to meeting the GHG mitigation commitments of their respective countries: to achieve net-zero by 2050 for Australia, the ROK, and New Zealand; and by 2060 for the PRC, Indonesia, and Kazakhstan. In addition, all of these economies are also aiming for significant GHG reductions by 2030. This is noteworthy especially for the PRC, Indonesia, Japan, the ROK, and Australia, which are the world’s first, sixth, seventh, 13th, and 15th largest emitters of GHGs, respectively (European Commission 2024). In terms of scope and coverage, the ROK’s ETS is the most comprehensive, as it includes all of the GHGs nominated in the Kyoto Protocol. New Zealand’s ETS is also comprehensive, though it excludes biogenic methane, which is a major emissions category for that jurisdiction. Most of the other national ETSs focus primarily on CO2 emissions. The share of total emissions covered by ETSs ranges from a low of 26 percent to 29 percent (Australia and Indonesia) to a high of 88.5 percent (ROK). The ROK and New Zealand have the most comprehensive coverage in terms of sectors, while the other systems mostly focus on the energy sector, a major source of CO2 emissions.

There is very little auctioning of emissions allowances in any ETS in Asia and the Pacific. Allowances within the region’s ETSs are mostly given for free, especially for emissions-intensive and trade-exposed industries. In New Zealand’s ETS, 54 percent of allowances were offered for auction in 2022, but none was sold, since the clearing price was lower than the reserve price [17]. With regard to allowance markets, only two ETSs (the ROK and New Zealand) had a long enough time series for prices. Allowance prices have been low in the ROK and moderate in New Zealand, especially as compared to the ETS of the European Union (EU). Additionally, in line with the experience of the EU’s ETS, allowance prices in the ROK and New Zealand have shown volatility. In the latter, prices fell to practically zero ($2) in 2013 soon after the announcement delinking the New Zealand ETS from Kyoto markets but prices have been mostly rising since then.

LESSONS FOR ECONOMIES IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Developing an ETS should be an exhaustive process, with pilot projects and policy flexibility. This approach can be observed in the case of the PRC, which undertook ETS experimentation during the early 2010s, yielding pilot systems that were diverse and instructional. These early ETSs spanned the political and business hubs of Beijing and Shanghai, the sprawling industrial municipalities of Tianjin and Chongqing, the manufacturing locus of Guangdong province, the iron and steel center of Hubei province, and the special economic zone of Shenzhen. Based on the pilot schemes, the PRC’s State Council released guidelines for accelerating the establishment of a national carbon market in 2017 and the nation-wide ETS was introduced in 2021. With guidelines again updated in 2024, the PRC’s national ETS is becoming a more impactful policy instrument [1]. Economies in Asia and the Pacific can learn from the PRC’s progressive implementation and ever-evolving ETS, and some are taking similar approaches to increasing scope and ambition over time. For instance, Thailand’s Greenhouse Gas Management Organization has operated a voluntary ETS since 2013, focusing on the development and testing of monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems, setting caps and allocation procedures, and establishing trading infrastructure for 12 sectors with high GHG emissions. Meanwhile, Indonesia and Viet Nam both have three-phase plans that expand in coverage, compliance obligations and potential impact through the 2020s. Prospective carbon markets elsewhere in South Asia and Southeast Asia will likewise go through progressive development stages if they are enacted.

The benefits and challenges of efficiency-based systems should be closely observed. The PRC, for example, has deployed efficiency-based targets in its ETS because such targets can be adapted to higher levels of economic production and aligned with broader PRC climate targets that lack an overall cap. Indonesia initiated an efficiency-based ETS in early 2023, focusing on power sector facilities with over 100 megawatts of production capacity. India’s Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme may evolve into a compliance-based ETS and is also based on efficiency targets. It is likely that other developing economies in Asia and the Pacific will pursue this route, given their growth ambitions. However, while the impetus for efficiency-based targets is clear, such targets may limit the ability of an ETS to significantly curb absolute emissions. ETS designs should therefore seek to reduce these risks through broad coverage and steadily tightening benchmarks. Economies should incorporate clear timelines and strategies for ensuring the emissions impacts of their ETSs and for transitioning to mass-based systems.

Institutional and regulatory frameworks are pivotal to the smooth operation of an ETS. When developing their ETSs, economies of the Asia and Pacific region should dedicate significant resources to developing and refining the MRV systems that strengthen data management and accuracy. Legal mandates should be developed for facilities to report their GHG emissions data to ensure accurate emissions tracking and reporting, which will enhance system credibility and environmental integrity and lead to effective enforcement.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Developing economies can use international carbon markets to meet domestic climate goals. With the finalization of the Paris Agreement Rulebook, many countries are operationalizing international carbon markets under Article 6 as well as engaging with VCMs. Although developing economies in Asia and the Pacific are mostly exploring avenues to export carbon credits, there is also potential for them to meet their climate ambitions by buying credits through international carbon markets. This could occur when an economy has projected that it may not reach its NDC targets (especially when these targets have been recently lifted) or when purchasing credits proves to be cheaper than domestic mitigation efforts (which may have high marginal abatement costs). Assuming that using public funds to purchase carbon credits is politically challenging, this task can be delegated to the private sector. For instance, economies with a high domestic carbon price may decide to tighten the cap of their ETS but allow for private entities under the cap to purchase international carbon credits (ITMOs), since this may constitute a more cost-effective alternative to high ETS prices. This has been the case in Indonesia.

The Asia and Pacific region have extensive experience in carbon market mechanisms. Approximately 80 percent of all CDM projects are based in Asia and the Pacific [20]. While project developers and validation and verification bodies can draw on experiences from the CDM, host economies have less to build on since Article 6 requires greater host involvement and higher institutional and MRV requirements. Japan’s Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) is a forerunner to Article 6.2 and around 90 percent of all JCM projects are hosted in the region. Developing economies in Asia and the Pacific can draw on experiences from the JCM as a bilateral approach.

The region has work to do in scaling up involvement in international carbon markets. Some of the existing challenges include: (i) lack of national strategies and frameworks for engagement with international carbon markets; (ii) ineffective governance systems including lack of inter-ministerial coordination as well as lack of mandates and legal instruments; (iii) lack of institutional capacity and/or skills of personnel to negotiate bilateral agreements; and (iv) lack of the carbon market expertise required to manage domestic processes and procedures for engagement in international markets.

National carbon market strategies are a vital catalyst for international engagement. Alongside enhancing institutional capacity and technical readiness to participate in international carbon markets, an important first step for many economies is to develop holistic national carbon market strategies [11]. To engage strategically in carbon markets, policy makers need to weigh the benefits of selling mitigation outcomes to attract carbon finance against the need to meet their NDC targets. Evaluating this trade-off requires a long-term strategy that aims to achieve NDC targets and informs engagement with Article 6, including guiding principles and criteria for mitigation outcomes to be eligible for international transfer.

Such a strategy must embrace the interrelationship between various carbon markets and cover management of both the compliance and voluntary markets. For instance, buyers in a VCM may wish to have carbon credits (ITMOs) that have authorization and cannot be used toward a host economy’s NDC targets. Another type of integration can occur when domestic carbon crediting mechanisms are used for Article 6.2 transactions, which may require new regulations and legal frameworks.

The NDC accounting aspect of Article 6 is critical to effective market integration. For economies to engage with international carbon markets, they need to have a framework outlining the sectors and types of mitigation activities from which they will allow ITMO exports. This, in turns, requires an understanding of how the NDC system will be implemented. The framework also needs to describe administrative procedures to manage ITMO authorization, tracking of ITMOs, and their accounting (corresponding adjustments).

Governments may consider what actions need to be taken to promote voluntary market activities within their jurisdiction and may consider regulating such markets.

ASSESSMENT OF LINKAGES BETWEEN NATIONAL ETS OF ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIES AND THE CROSS-BORDER CARBON MARKET MECHANISM

Some nations in Asia and the Pacific, including the People’s Republic of China, Japan, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea, and New Zealand, have implemented emissions trading systems (ETSs) as a way to curtail their greenhouse gas emissions. The prospect of linking these individual ETSs to establish a cross-border carbon market presents the potential for climate, economic and political benefits. The research study focuses on the theoretical aspect and underpinnings of ETS linkages and examples of implementation in practice. An assessment on the compatibility among the five Asia and the Pacific ETSs and the proposed framework that encompasses the design elements of a cross-border carbon market has been made. In addition, the hurdles and challenges associated with linking ETSs and present a set of recommendations that underscore the imperative of enhanced intercommunication, collaborative effort, and policy harmonization have also been delineated.

The imperative of tackling the global climate crisis necessitates the establishment of an internationally coordinated carbon pricing framework that holds the potential to realize climate goals while minimizing economic costs. However, prevailing endeavors in climate mitigation remain fragmented, as a result of countries’ divergent climate ambitions. For example, many nations have implemented emissions trading systems (ETSs) as a cost-effective instrument to incentivize the transition toward a low-carbon economy. But these carbon markets remain predominantly insular, lacking concerted initiatives to forge a cohesive pricing regime.

Linking cross-border carbon markets has the potential to deliver climate, economic, and political benefits for all participating countries. The primary advantage relates to lowering emission reduction costs. The existence of heterogeneous marginal abatement costs means the cross-border exchange of carbon allowances can cut compliance costs for all parties [19]. Furthermore, linking markets can improve welfare via gains from trade [26] and through enhanced terms of trade. The advantages are heightened where the linkages are between developed and developing country markets. In such scenarios, permit-exporting nations stand to gain from the sale of permits, whereas permit- importing nations benefit from reduced compliance costs. In this way, mutual economic advancement is fostered [24].

Linking carbon markets can yield financial and operational improvements, for example through price discovery, liquidity provision, and risk management. It is pertinent to note that a carbon market has similar characteristics to a financial market. ETS linkage heightens market liquidity by augmenting the pool of market participants and instituting an inclusive and transparent environment. Introducing more market participants allows the carbon price to reflect public information better, thereby enriching the price discovery process. Furthermore, the linkage can mitigate price volatility within the carbon market [19]. Additionally, it empowers nations to collectively bear the brunt of the price volatility, thereby enhancing market efficiency.

ETS linkage can potentially ameliorate the pressing concern of carbon leakage, which has gained prominence in a world marked by fragmented climate policies. Given the heterogeneous nature of stringency levels of climate policies, regulated firms may contemplate relocating to jurisdictions with less stringent climate regulations, thus undermining the collective global endeavor to curtail carbon emissions. Notably, the convergence of carbon prices in linked ETSs mitigates the risk of carbon leakage. In addition, ETS linkage fosters the standardization of carbon market designs and consequently contributes to mitigating carbon leakage concerns.

ETS linkage can exert a fortifying influence on climate ambition. Successful linkage can heighten mutual trust among nations and mitigate concerns regarding free-riding in climate mitigation. Moreover, it fosters domestic business engagement and engenders public acceptance of climate policies. More widespread acceptance of climate policies means policy makers can augment their bargaining power in dealing with domestic interest groups that are against climate policies, and are emboldened to take more ambitious climate actions.

Asia and the Pacific are the world’s most substantial contributor to carbon emissions and responsible for 52 percent of global emissions. Five prominent ADB member countries within Asia and the Pacific, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Japan, Kazakhstan, the Republic of Korea (ROK), and New Zealand, have launched compliance-based carbon markets, such as the national ETS of the PRC, to curb their ever-increasing carbon emissions. However, these countries have not yet formally linked their ETSs.

Despite the potential benefits, linking ETSs within Asia and the Pacific faces substantial obstacles, primarily related to concerns about ETS compatibility. The critical factors shaping an ETS including participation, cap, scope, allowance, allocation, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV), market stabilization mechanism, and compliance and enforcement exert a profound influence on the degree of compatibility and comparability these ETSs exhibit [18].

However, cross-border carbon market linkages between Asia and the Pacific countries have yet to materialize. The PRC, Japan, Kazakhstan, and the Republic of Korea (ROK) have ETSs in force along with regional credit mechanisms. Pakistan is actively formulating detailed frameworks. Japan, while establishing bilateral linkages domestically, has entered the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) agreement with Mongolia, permitting Japan to incorporate emission reductions from Mongolia to fulfil its own NDCs. Australia, the ROK, and Singapore have individually signed bilateral cooperation agreements with developing nations under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement. Additionally, international and independent mechanisms like the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), the Gold Standard (GS), and the American Carbon Registry (ACR) produce credits that can be utilized for voluntary commitments and participation in international compliance schemes.

LINKING MECHANISMS AND ROADMAP

A direct linkage can be classified into one-way and two-way linkages, depending on the mutual recognition of allowances or credits. In a one-way linkage (unilateral linkage), one system allows covered emitters to utilize allowances or credits from another system; however, the latter system does not reciprocate this mechanism. Conversely, a two-way linkage (bilateral or multilateral linkage) occurs when both participating systems mutually accept allowances or credits from each other. This distinction in direct linkage mechanisms delineates the nature and dynamics of carbon market interactions between ETSs.

One and two-way linkages between ETSs yield different consequences, primarily related to the transfer of emissions between countries and changes in carbon prices [19]. If a country allows its covered entities to procure carbon allowances from less expensive overseas sources for domestic compliance, it will increase domestic carbon emissions. This, in turn, leads to a decrease in the marginal abatement cost and the carbon price within that country. Conversely, in the allowance-exporting country, carbon emissions will be further reduced, leading to higher marginal abatement costs and carbon prices. Consequently, the allowance-exporting country will be compensated financially by the importing country. Importantly, one-way linkage ensures the carbon price in allowance-importing countries does not surpass that in allowance-exporting countries. In contrast, a two-way linkage permits the unhindered exchange of carbon allowances between two countries, leading to the eventual convergence of carbon prices in both nations.

For the compliance markets of the five Asia and the Pacific countries, it would be more advantageous to embrace bilateral or multilateral linkages. While unilateral linking is common practice in connecting compliance markets with voluntary markets, it is comparatively less extensively used when linking two compliance programs. The adoption of bilateral or multilateral linkages offers several advantages. Unilateral linkage, while it can lower the marginal abatement cost in allowance-importing countries, also results in unilateral funds transfer. A unilateral linkage is also ill suited to adapt to situations where marginal abatement costs change. For instance, the ROK and New Zealand have high carbon prices; Japan and Kazakhstan have low carbon prices. If a unilateral linkage is designed based on existing marginal abatement costs, it may become obsolete if the cost dynamics change over time.

The primary objective of ETS linkages is to establish a consistent carbon price signal. Consequently, the ideal approach is to employ multilateral linkages that encompass as many countries as possible. However, given the intricacy involved in establishing an extensive cross-border carbon market linkage, this goal is unlikely to be achieved in the short term. Establishing a mature Asia and the Pacific cross-border carbon market should be a systematic process. Specifically, in the short term, each compliance market should be further developed and prepared for linkage. In the medium term, the compliance markets will be linked indirectly through the voluntary markets. In the long term, the compliance markets will be linked directly, with restrictions on the conditions under which allowances can be used for compliance. Eventually, this will transition to an unrestricted cross-border carbon market.

FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE IN ASIA PACIFIC

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges facing policy makers worldwide, and the stakes are particularly high for Asia and the Pacific. Climate change threatens long-term growth potential, livelihoods, and well-being in all countries in the region. Temperatures are rising faster than in any other region. It is already the region most susceptible to weather-related natural disasters, such as hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires, which will become more frequent and severe. Rising sea levels could directly affect a billion people in the region by mid-century, potentially submerge many mega cities, and pose existential threats to some Pacific island countries.

Asia and the Pacific are critical to tackling climate change. Considering that the region has the majority of the world’s population, is the main driver of global growth, and includes many countries with substantial development needs, Asia and the Pacific has not surprisingly become the main greenhouse gas (GHG)-emitting region, producing about half of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions currently. The region also accounts for about half of world GHG emissions from the agricultural sector. Excluding China, however, the region’s cumulative and per capita CO2 emissions remain considerably lower than those of North America and Europe. At a time when the entire world needs to step up mitigation efforts, greater emissions reductions from China, India, and other large CO2-emitting economies in Asia and the Pacific will need to play a key part of the global effort.

Fiscal policy plays a critical role in responding to climate change. Climate change mitigation, which refers to efforts to reduce or prevent emissions of GHGs, can be achieved by well-designed tax policies that raise the price of carbon, together with non-tax instruments such as emission trading systems, fee bates, or regulations. Climate change adaptation refers to adapting to the effects of climate change and minimizing damage from climate-related natural disasters. This typically requires an increase in government spending, among other actions, which needs to be accommodated under the overall fiscal framework of a country. Further, fiscal policy can facilitate the transition to a greener, low-carbon economy by investing in climate-smart infrastructure such as renewable power generation and supporting research and development (R&D) in climate-smart technologies.

Although Asia and the Pacific’s adaptive capacity is merely average, it faces the highest climate risks. All countries in the region have the scope and need to increase their adaptive capacity, but the gap is largest for low-income countries and Pacific island countries, many of whom face the highest climate risks.

This calls for mainstreaming adaptation into national budgets and fiscal strategies. While some progress has been made, for example in identifying climate-related spending, most countries in the region have yet to fully cost and prioritize their adaptation plans.

Investing in adaptive infrastructure can yield high returns (for example, greater private investment, less damage and economic disruption from disasters, lower disaster recovery spending, and a quicker rebound in economic activity), especially if efficiently undertaken.

Strengthening adaptive capacity will entail higher public investment spending on average about 3.3 percent of GDP annually for the region, but much higher for many, especially some Pacific island countries. While for some countries this may entail only upgrading new investment projects to make them more climate resilient, which is relatively inexpensive, for others, it may mean retrofitting existing climate-exposed critical assets and/or developing coastal protection infrastructure, both of which are significantly more expensive. For countries with limited fiscal space, options to finance the additional investments include greater domestic revenue mobilization (for which there is considerable scope in the region) and/or improving spending prioritization and efficiency.

Concessional financing will be critical for low-income countries with large adaptation investment needs and dwindling fiscal space due to the COVID-19 crisis, especially Pacific island countries, where adaptation needs tend to be large relative to their size of the economy and capacity to mobilize domestic revenue.

ROLE OF IMF IN ACHIEVING FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY AMIDST CLIMATE CHANGE IN ASIA PACIFIC