-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Solomon Titus Gushibet*

Corresponding Author: Solomon Titus Gushibet, National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS) Kuru, Jos-Plateau, Nigeria.

Received: July 10, 2025 ; Revised: August 20, 2025 ; Accepted: August 23, 2025 ; Available Online: August 26, 2025

Citation:

Copyrights:

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

The study examines the use of local currencies for trade facilitation within the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). It explores the adoption of Pan-African Payment Settlement System (PAPSS) in facilitating intra-African trade. The study adopts qualitative research method and descriptive analytical approach using tables, figures, ratios and percentages. It was found that the use of local currencies has facilitated intra-African trade, and the introduction of PAPSS has helped Africa avoid converting to hard currencies thereby saving approximately US$5 billion annually in transaction costs. It was also found that cross border transactions were previously incurring 10-30% in costs under the old model, but PAPSS has reduced that cost to around 1% with transaction speed of less than 120 seconds through instant payment thereby simplifying trade in Africa. However, intra-African trade remains low relative to other regions of the world as a result of numerous challenges such as poor infrastructure, high transport costs, weak border governance, amongst other constraints. The study recommends the establishment of regional currency swap arrangements and convertibility frameworks, strengthening the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, investing in currency stabilization mechanisms, improving financial and foreign exchange market infrastructure amongst other recommendations.

Keywords: Africa, Trade, Free trade, Local currencies, Trade facilitation, Growth

JEL Classification: F15, F31, O55, E42

INTRODUCTION

Trade is as old as human history and it remains one of the most transformative forces in modern times. It reshapes economies, redraws geopolitical landscapes, and redefines the path to development. It also fuels growth and innovation, and exposes deep inequalities and vulnerabilities. While some nations especially developed countries surge ahead, others struggle to gain equitable access to markets or diversify their economies beyond commodity exports. Many African economies still rely heavily on exporting raw materials to external markets rather than trading value-added goods within the continent. Only about 15-18% of Africa’s trade is with other African countries, compared to 60-67% in Europe and 40-58% in North America and Asia [1,2]. The idea of establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was to bridge this gap and fast-track trade and development in Africa.

AfCFTA is one of the most ambitious regional integration efforts in the world, and the use of local currencies instead of relying primarily on foreign currencies like the U.S. dollar or euro has major implications for trade costs, exchange rate risk, liquidity, and monetary sovereignty. Launched in 2021, it represents a transformative step towards economic integration across Africa with the goal of increasing intra-African trade from current levels (15-18%) to 50% or more by 2040 [3,4]. With 54 countries committed to reducing trade barriers and enhancing intra-African commerce, a critical question arises: Does the use of local currencies matter for trade and development in Africa? This question strikes at the core of trade facilitation, monetary policy, fiscal policy and sustainable development in Africa. One is curious to say yes; the use of African currencies matters significantly for the success of AfCFTA and broader trade-led development. It is worthy of note to envisage that while the transition from foreign-dominated transactions to local-currency-based trade will be gradual and complex, the likely long-term benefits - economic sovereignty, reduced costs, and enhanced regional integration which would free up money for Africa’s development, make it a strategic priority for African policymakers.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) seeks to deepen economic integration across Africa by creating a single market for goods and services. One of the critical challenges to fully realizing this goal is currency fragmentation. Most intra-African trade is still conducted in third-party currencies (primarily US dollar, Euro and Great British Pound), even between neighboring countries, thereby increasing transaction costs and exposure to currency volatility. Therefore, AfCFTA) was formed to facilitate trade and development amongst African countries through intra-African trading initiatives. AfCFTA Agreement represents an Africa Union (AU) attempt to provide platforms for Africans to use an African solution to an Africa problem [5]. The aim of AfCFTA is to achieve a single continental market, a market that promotes inclusive and sustainable development for African countries through intra-African Trade [6-8].

Most intra-African trade transactions are conducted in foreign currencies, particularly the US dollar, euro, or British pound. This reliance leads to high transaction costs, currency conversion delays, exposure to external shocks, exchange rate risks, and limited access to hard currency for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) thus stifling trade and development in Africa. This hinders trade among African countries by making cross-border transactions more expensive and inefficient. This study believes that promoting trade in local or regional African currencies can reduce these costs and encourage more intra-African commerce. Using African currencies, particularly through mechanisms like currency swap arrangements or regional payment systems, could support the smooth flow of trade and enhance liquidity within the continent. The dominance of foreign currencies has escalated the challenges in trading activities across African borders. This would undermine AfCFTA's objectives to boost trade, industrialization, and economic inclusion in the region. This economic problem has provoked the study. Escalating poverty and the rising cost of living in the continent is the problem that led to the choice of this topic. The following research questions substantiate the problem:

From the foregoing research questions, the objectives of the study are to:

The work is divided into nine sections. The foregoing is the introductory section one. Section two gives an overview of AfCFTA, local currencies and digital trade. Section three deals with the conceptual clarifications as section four focuses on literature review. Section five explains the theoretical framework of the study. Section six outlines the methods and materials used in the study. Section seven commits to results and discussion as section eight highlights the thematic analysis of responses. Section nine concludes the study with recommendations.

OVERVIEW OF AFCFTA, LOCAL CURRENCIES AND DIGITAL TRADE

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is strategically positioning Africa to tap into a US$712 billion digital trade market by 2035, leveraging key partnerships and trade-enabling infrastructure to deepen continental integration and economic sovereignty, as the protocol on Digital Trade is central to AfCFTA’s strategy for unlocking the potential of Africa’s growing digital economy [9]. He further stated that this is a significant market for Africa to harness, which is estimated to be over US$712 billion by the year 2035, presenting opportunities for young entrepreneurs, investment in data centers, the commercialization and movement of data, and the development of digital public infrastructure.

The support of Afrexim bank is critical to the success of AfCFTA which requires trade finance tools, support for industrial development, green trade, and green industrialization. AfCFTA collaborated with Afrexim bank to introduce the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), which enables intra-African payments in local currencies capable of reducing dependence on foreign currencies such as the US dollar and lowering transaction costs. It implies that trading in foreign currencies like US dollar, euro and British pounds between African countries is no longer sustainable. The use of local currencies has become important if Africa’s economic sovereignty is to be guaranteed. This will also guard against ever-shifting global geopolitical tensions that transmit shockwaves that affect payment systems across borders globally.

According to Wamkele [9], US$10 billion has been mobilized under the AfCFTA Adjustment Fund to support countries implementing the agreement, with an initial ZIP package of US$1 billion. Furthermore, a US$1 billion AfCFTA Automotive Fund has been established to support component manufacturers and vehicle assembly on the continent. Wamkele [9] observed that the sector could generate US$46 billion by 2035 if well-supported. E-Tariff platform, the Rules of Origin Manual, and the soon-to-be-launched Transit Guarantee System are additional initiatives introduced by AfCFTA in order to simplify trade procedures and boost trade amongst member countries. It means that a functional and legally binding multilateral African trading system which includes protocols on investment, competition policy, and digital trade, have become inevitable.

CONCEPTUAL CLARIFICATIONS

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is a trade agreement aiming to create a single African market by eliminating tariffs and boosting intra-African trade. Trade could be described as the exchange of goods and services across international borders, while development refers to the economic growth and improvement in living standards, particularly in low- and-middle-income countries. Together, global trade and development represent a dynamic relationship where trade acts as a potential engine for economic growth and poverty reduction thereby entrenching development. Trade has helped countries like China, South Korea, and Vietnam lift millions out of poverty [10-12]. Trade often brings new technologies and practices, and enhances productivity [13]. Export-oriented sectors often create employment opportunities and access to a wider variety of goods at lower prices [14].

Trade facilitation refers to the simplification, modernization, and harmonization of international trade procedures. It aims to make the movement of goods across borders faster, cheaper, and more efficient by reducing bureaucratic delays, improving customs procedures, and enhancing transparency. Trade facilitation occurs when a regional bloc has a streamlined customs process, standardized documentation, use of technology e.g., electronic data exchange, improved border infrastructure and coordination among border agencies. Overall, trade facilitation helps reduce trade costs, increases competitiveness, and supports economic growth in the short-run and economic development in the long-run.

Local currencies are forms of money that are used within a specific community, region, or country and are not widely accepted outside that area. They are typically issued and regulated by local authorities, organizations, national governments or regional cooperation. Local currencies aim to boost local economies, support micro and small businesses, and reduce dependence on foreign currencies or national economic fluctuations.

LITERATURE REVIEW

IMF [15] made simulation analyses for 45 African countries and found that full tariff elimination plus a 35% cut in non‑tariff barriers has boosted welfare of member countries by roughly 2-4%, with most gains stemming from easier non-tariff barriers. Impact of welfare payments on standard of living is buttressed by Umeghalu, Machi, and Chukwuka [16] as a macroeconomic strategy aimed at sustainably improving citizens’ living standards. This macroeconomic strategy involves fiscal and monetary policies. IMF [15] alluded that AfCFTA has strong potential to significantly increase intra‑African trade and embed the continent in regional value chains, but only if coupled with infrastructure, financial markets, and security enhancements. Combining Doing Business and OECD indicators, Melo [17] estimated that AfCFTA countries could reduce import customs delays by approximately 65 H, cutting trade costs by 3.6-7%, and reduce export delays by roughly 42 h, thereby increasing exports by about 8%.

Empirical literature such as Rose [18], Masson and Pattillo [19] consistently reveal that currency unions and shared currencies boost bilateral trade sometimes doubling or tripling trade volumes. Exchange rate volatility also diminishes trade [20]. Using a gravity‐model analysis of bilateral trade data from 1970 to 1990, Rose [18] found that countries sharing a currency, like those in formal currency unions - trade approximately three times as much as those that do not. Gravity-model studies (2008-2023 panel) further showed that regional trade agreements (RTAs), GDP size, contiguity, and shared official language positively drive bilateral trade; geographical distance becomes less significant post‑RTA [21].

The Pan‑African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), launched in 2022, allows payments between African countries in local currencies, slashing transaction costs from 10-30% down to about 1% of trade value. This could save Africa approximately US$5 billion annually. PAPSS now includes 15 countries and 150 banks. International Finance Corporation (IFC) and G20 support echoes the overarching development motive - reducing dollar-dependency to boost intra‑African trade [22]. So far, transaction volume through Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) increased by over 1,000 percent between 2024 and 2025, reflecting increased adoption of the payment system [23]. It is estimated that PAPSS could bring informal trade worth US$50 billion into formal economy in Africa [24].

Several studies such as Tsowou and Davis [25], Okeke and Ameh [26] have identified the challenges undermining AfCFTA’s potential to include landlocked states facing high transport costs, weak customs, security concerns, weak border governance, poor logistics, fragmented governance, overlapping communities, political instability, and corruption as major obstacles to AfCFTA effectiveness. Stricter origin requirements risk might deter businesses from using AfCFTA preferences; implying that simplicity and transparency are key to foreign trade [25]. Other challenges include inefficient customs systems, high trade costs that limit MSME market entry, insistent conflict and rural instability, persistent food insecurity which prevents smallholder farmers from accessing markets [9]. Concrete collaboration between political leaders in Africa and development finance institutions to address these obstacles has become most desirably a compelling need.

In Nigeria (Africa’s most populous nation), international trade has contributed significantly to development, given its trade relations, open trading policies, and exchange rate gains [27]. Although Nigeria’s exports have been largely dominated by primary products (crude oil), export has been the engine of growth with multiplier effects on market expansion, job creation, and GDP [28]. Nevertheless, Nigeria has poorly performed on trade facilitation measures [29]. Nigeria also fared badly on global competitiveness indexes, and ranked 114th out of 189 countries trading across borders and scored 2.54 out of 5 in the global logistics index. It also dropped from 99th to 127th out of 133 countries on the global competitiveness index [6,29]. From the foregoing, Nigeria (Africa’s biggest oil producer) has to wake up and be strategic in its approach for it to compete favorably with other African countries and become a major player and significant beneficiary of AfCFTA.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The study tracks its theoretical foundation in two trade theories. The Size and Distance Theory of Trade and the Technological Theory of Trade. The size and distance theory consider the effect of distance on international trade. It considers transport costs and distance as barriers to trade between countries. This is relevant to the intensity of trade flows and agrees with custom union theory of regional integration. Custom unions are normally formed among contiguous states. The theory states that the nearer the trading partners the higher the flow of trade, ceteris paribus. Linnemann and Tinbergen postulated that size and distance are key determinants of external trade because trade will vary directly with size (population and national income) and inversely with the distance between two trading countries [30].

The technological theory is the dynamic, contemporary comparative advantage theory that involves innovation, imitation and product cycles. The theory is more applicable to manufactures, emphasizing the role of innovations and technological advances to gain in trade over primary product exports. It postulates that knowledge and technical ingenuity are important determinants of trade whereby a nation may innovate or imitate a product. Posner [31] identified the existence of imitation gap as Vernon [32] recognized innovation gap and product cycle as critical to trade. The basic hypothesis of these sub-theories is that a country which innovates a good will first surmount the domestic market, and will later start exporting it, at least for a while before the commodity is imitated by other countries. The theory of the innovation gap asserts that a country that is a leading innovator will have a comparative advantage in the export of the new value-added, technically advanced products.

The theory of product cycle explains how the export pattern changes as a product mature. Four distinct phases are identifiable in the product cycle after a new product is introduced as a result of some technological innovation. During the first phase, the product conquers the domestic market. During the second phase, it is exported to other countries. With successful exportation and rising demand, the producers may be faced with the need to move production closer to the foreign market (the third phase), as the foreign market may now be large enough to permit large scale production abroad. This will cut down transport costs with considerable cost savings.

The two theories have their place, basis and relevance in this study. The size and distance theory for instance, supports the idea of regional economic integration among contiguous states to take advantage of their closeness and engage as strong trading partners. This is theoretically true and politically viable of AfCFTA member countries to form a free trade area that brings the 54 African countries together for intra-African trade. However, member countries that engage in innovation to produce superior products will become significant beneficiaries of the union. They will not only expand their superior export commodities, but coral a significant share of the continent’s total trade thereby impacting on growth and development of their own national economies. This is in consonance with the technological theory of trade.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The study adopts qualitative method and descriptive-analytical approach using such tools as tables, figures, ratios and percentages. Primary sources of data collection through expert interviews were used while secondary sources of information and data included government reports, international financial institutions (World Bank and IMF) data, media publications, and previous scholarly works. Purposeful sampling which is useful in qualitative research was employed to select respondents who are knowledgeable and experienced in the subject area rather than generalizing to a population. Key Informant Interview (KII) was utilized as the instrument of collecting primary data from a mix of 10 experts comprising policymakers, civil society actors, international traders and academics. The scope of the study covered intra-African trade beginning from 2021 and terminating in 2025. The analyses were general and thematic.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

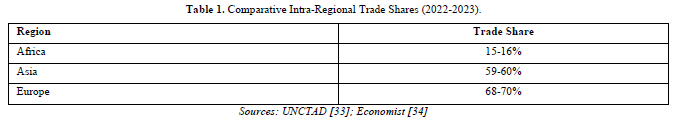

Continents across the globe undertake intra-regional trade in order to fast-track growth and development of their countries. Table 1 shows a comparative intra‑regional trade shares across Africa, Asia and Europe from 2022 to 2023.

From Table 1, it is clear that Africa remains significantly behind other regions in intra‑regional integration. While Asia and Europe have reached about 60% and 70% respectively in terms of intra-regional trade shares by 2023, Africa lagged behind with a trifling 16%. It implies that even with the introduction of AfCFTA in 2021, the Africa region remains the weakest in terms of intra-regional trade. All hope is not lost as full implementation of AfCFTA could lift intra-African trade by over 50%, contributing US$450 billion to Africa’s GDP by 2035, and reducing extreme poverty by 30 to 50 million people [35].

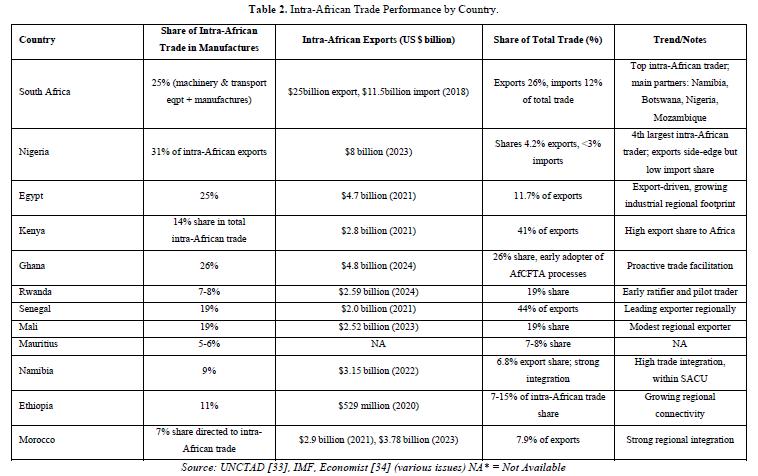

Table 2, presents a country-by-country tabular analysis of general intra‑African trade performance including trade in manufactures among AfCFTA member countries, using the most recent available data across various metrics. South Africa remains the dominant manufactured goods exporter, with machinery, vehicles, and equipment leading its intra‑African trade. As top intra-African trader, its main partners include Nigeria, Namibia, Botswana, and Mozambique. Nigeria and Egypt, despite being commodity-heavy, still have strong intra-continental manufacturing-oriented trade components (about 25-31%). Nigeria is the 4th largest intra-Africa trader with exports side-edge but low import share. Nigeria’s exports to Africa more than doubled in 2024, to N8.74 trillion from N3.71 trillion in 2023 (though a mere 4.2% of its total exports and 3.0% of its total imports), making Africa an emerging export destination [36]. It could be deduced that the top country contributors in 2024were; South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria - the key exporters of manufactured, industrially processed goods within Africa. Smaller economies (Kenya, Ghana, Senegal, Rwanda, Mali, etc.) typically export a higher share of manufactured goods from +7% up to 26%. From the foregoing analysis, manufactured goods constitute a meaningful and growing slice of intra‑African trade under AfCFTA, representing around a quarter of exports. Leading countries like South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria drive this, but numerous others show strong industrial trade potential. These statistics imply that Africa is gradually becoming strong in terms of manufactures and economic integration.

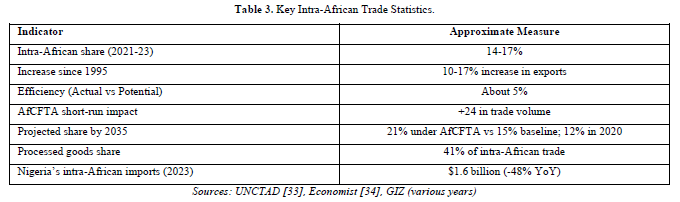

It is indicated in Table 3 that intra-African export share reached 17% in 2023, compared with 10% in 1995. Although slowly rising, intra-African trade remains low relative to other regions; around 15-17% of total African trade by the early2020s; with only modest growth since the 1990s. It is estimated that intra‑African exports are at only about 5% of potential capacity, highlighting huge inefficiencies. This could be attributable to limited access to finance, infrastructure bottlenecks, and high trade costs, especially for distant country pairs. Despite growth, intra‑African trade remains below its potential due to modest share of total trade and efficiency gaps. This agrees with the submission by Tsowou and Davis [25], and Okeke and Ameh [26] as shown in the extant literature.

In terms of short-run impact, Table 3 suggests that AfCFTA could boost intra-African trade by 24% in trade volumes. This means that long-term gains will likely be higher. Without additional policy steps (pre-AfCFTA), intra‑African share would modestly rise from 12% in 2020 to 15% in 2035; but with AfCFTA, the forecast is 21% by 2035. Table 3 also indicates that 41% of intra-African trade comprises processed goods when compared to just 17% in extra-continental exports. This is on a positive node, suggesting greater value addition when African countries trade among themselves because higher trade correlates with improved GDP per capita and stronger financial markets. This further corroborates the findings by Ogbaji and Ebebe [28]. On the import side, for instance, Nigeria’s intra-African imports fell to US$1.6 billion, a drop >48% from 2022, ranking sixth in Africa. This is an indication that the giant of Africa (Nigeria) could do better.

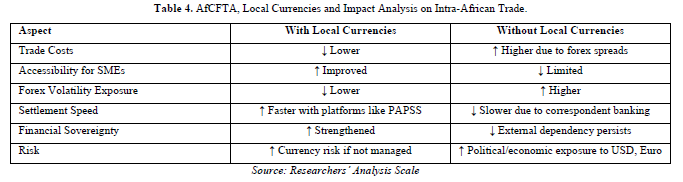

Table 4 shows that the use of local currencies in intra-African trade would reduce trade costs among African countries. It implies that trading in local currencies eliminates multiple conversions and reduces costs of transaction across national borders, unlike hard currencies like the US dollar that incurs huge conversion fees, bank charges, and cross-border payment costs which makes intra-African trade expensive and unsustainable. The use of local currencies in intra-African trade would facilitate accessibility to MSMEs’ products as they benefit from trading at lower cost. Ordinarily, MSMEs find it difficult to absorb high forex fees, and they account for about 80% of businesses in Africa but are underrepresented in cross-border trade due to such barriers [37]. Lower transaction costs and easier payments would increase trade volumes and liquidity.

The Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) allows instant cross-border payments in local currencies. Table 4 indicates the settlement speed in trading transactions which is faster with platforms like PAPSS. This implies speedy settlement of payments thereby enhancing trade facilitation in Africa. This is in consonance with the findings by Masson and Pattillo [19], and Rose [18] who, in the extant literature, found that customs unions and shared currencies boost trade. PAPSS could facilitate real-time payments across African countries in local currencies, whereby traders pay in local currency as the system settles payments via central bank clearing. This has already been piloted successfully among West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ) members. It means that the need to strengthen and patronize PAPSS with every sense of patriotism by citizens of member countries is imperative. This will eliminate the need for third-party currencies and can help resolve settlement issues in trade in the Africa region. This will result in a faster, cheaper, and safer transactions directly and in support of AfCFTA's goal and mandate. Again, encouraging the use of African currencies could strengthen monetary sovereignty and reduce vulnerability to global financial fluctuations. Countries can better align monetary policy with national and regional development goals.

Additionally, the following specific findings on the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) were obtained:

Savings: between US$18 million and US$58 million was made on transaction of US$200 million

From the foregoing analysis, the following benefits of PAPSS are identifiable:

Despite the advantages of PAPSS, Table 4 reveals that there could be challenges such as foreign exchange volatility exposure in the process of deploying African currencies. Many African currencies are volatile or suffer from inflation, making them unattractive for trade settlement. It is likely that traders may resist using weaker currencies or face price uncertainty. For example, Zimbabwean dollar or Nigerian naira volatility may deter their use in cross-border trade. This has corroborated the submission by IMF [20] that exchange rate volatility diminishes trade. Moreover, most African currencies are not freely convertible, and requires central banks to develop bilateral/multilateral clearing mechanisms or use units of account such as African Monetary Fund proposals. Based on currency strength, stronger economies in Africa such as South Africa, Egypt and Morocco may dominate trade balances, creating pressure on weaker economies’ forex reserves if not well managed.

Technical and infrastructure constraints are eminent. Limited digital payment systems, low interoperability between banks, and lack of centralized currency clearing could pose a challenge to the initiative. PAPSS is a start, but needs full integration and trust among all 54 participating countries. There is likelihood of potential political resistance because ceding control over currency-related matters, especially to regional institutions, could face nationalistic opposition. For instance, delays in implementing the West African single currency (Eco) highlight political hurdles. Infrastructure gaps (roads, rail, ports), non-tariff barriers (customs delays, documentation), and visa restrictions are slowing trade within the free trade area as political instability and conflict in parts of Sahel and Central Africa is deterring investment within the free trade area of AfCFTA.

Thematic Analysis of Interview Responses

Key Informant Interview (KII) questionnaire was administered to a diverse group of 10 experts who are knowledgeable and experienced on international trade and regional integration. Based on the responses from the 10 key informants (2 policymakers, 2 civil society actors, 3 international traders, and 3 academics), we derived the following thematic insights:

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The use of local currencies within the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) holds significant potential for enhancing trade facilitation across the continent. By reducing reliance on foreign currencies, particularly the US dollar, local currency use can lower transaction costs, mitigate exchange rate risks, and improve liquidity for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). While challenges such as currency volatility and weak financial infrastructure remain, coordinated monetary policies, regional payment systems, and trust-building measures can make local currency trade a viable path toward deeper economic integration and sustainable intra-African trade. By investing in implementation, fostering trust among member states, and focusing on value-added production, AfCFTA can become a true engine for African economic transformation, poverty reduction, and global competitiveness. Based on the findings, the following recommendations were made for member countries of AfCFTA to implement individually and collectively:

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :