-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Alfred Renger* and Monika Czirfuszová

Corresponding Author: Alfred Renger, Medical Care Centre Dr Renger/Dr Becker, Heidenheim, Germany

Received: May 1, 2022 ; Revised: May 10, 2022 ; Accepted: May 15, 2022 ; Available Online: May 20, 2022

Citation: Renger A & Czirfuszová M. (2021) Advertising and Investment for Medical Care Centres in Germany. J Nurs Midwifery Res, 1(2): 1-10.

Copyrights: ©2021 Renger A & Czirfuszová M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Abstract

Introduction: The medical care centre has become a well-established medical structure in Germany.

Aspects of the advertising and financial control have created whole new professions, both in the consultation and the concrete implementation of these fields of expertise.

Objectives: The medical care centre with its future-proof structure is now an integral part of these fields of expertise, and it can almost be said that the playing field that applied for single-handed and group practices before 2004 is now a thing of the past.

Methodology: Looking through recent literature reveals that there is currently a knowledge market on the topic of the ‘medical care centre’ and also a broad and active range of consultation services.

Results: Stakeholders in medical care centres need to focus on advertising, financial control and investment considerations to survive the fierce competition in the medical field.

Conclusions: Those who simply bury their heads in the sand and choose to believe that things will carry on as before may be in for a rude awakening, particularly when it comes to current healthcare policy issues that need to be addressed professionally.

Keywords: Advertising, Financial control, Investment, Medical care centre/s, Future-proof structure, Fields of expertise

INTRODUCTION

The medical healthcare structures that have arisen with the Medical Care Centres (MCCs) are only comparable to those of the Polikliniks (multi-disciplinary outpatient clinics) of the former German Democratic Republic. They have, however, become established as specialist medical units, referred to colloquially as ‘medicine from a single source’ and ‘under one roof’ [1-10]. Since the German Statutory Health Insurance Modernisation Act (GKV-GMG) of 2004 resulted in MCCs being established in outpatient care, there has been a constant battle over the distribution of resources between the various healthcare structures, in addition to the fundamental fee disputes between the various disciplines. In this confrontation, the MCCs are burdened twice over: First, as the ‘newcomers’, they are viewed with suspicion by the independent SHI-accredited physicians, who exercise decisive influence in doctors’ self-governance. Second, the assertion of legitimate interests is impeded by the fact that the SPD/Green government introduced the MCCs into the healthcare landscape before 2005 under the label of ‘promoting cooperation’. Although this was never a matter of fee advantages, MCCs are often assumed to receive higher fees than doctors in single-handed practices, as a form of promotion. The ‘cooperation bonus’ that MCCs and group practices receive on top of their standard service volume seems to be incontrovertible evidence of this.

The concept of the ‘treatment case’ reduces the income of MCCs. The ‘cooperation bonus’ is, however, (as every doctor thinking of setting up an MCC should know) a misleading term, as it always needs to be considered in the context of cases being counted as one course of treatment, a rule which has also applied since April 2009. The ‘treatment case’ described in the doctors’ fee schedule (EBM), which serves as the basis for calculating how fees are allocated for the majority of SHI-accredited doctors associations (KVs), results in structural financial burdens for cooperations that can mean noticeable reductions in revenue compared with work in a single-handed practice. MCCs are entitled to the ‘cooperation bonus’ for precisely this reason, and not, for example, because legislature and the KVs want to give MCCs a financial advantage. This ‘bonus’ does not generally fully compensate for the fee disadvantages resulting from basing payment on the treatment case, however, and is therefore not literally a bonus, in the sense of ‘extra income’ [11]. 57% of clinic bosses report being unable to invest sufficiently; in the 2016 survey, the figure was only 40%. The main reason for this - cited by 90% - is the lack of public funding from the federal states. This means that the Hospital Structure Act has only brought about minimal relief for the investment problems. 53% of clinic bosses name inadequate revenue from day-to-day operations as a further reason why they are unable to invest. The digitisation of hospital operations is evidently struggling to make progress: 91% of clinics spend less than 2% of their revenue on information technology, and 41% spend less than 1%. Nevertheless, 89% claim to have a digital strategy. This also seems necessary for their own security: two thirds of clinics have been the victim of hacking. To counter this, firewall protection has been stepped up almost everywhere. Roughly three quarters responded with emergency response plans and staff training. Only 31% increased the number of informatic (IT) staff [12].

CURRENT DEVELOPMENT

Drop in number of single-handed practices

The number of single-handed practices in Germany has declined in the past 10 years. More and more doctors are opting to carry out their profession jointly with colleagues in larger practice structures. The drop in the numbers of single-handed practices is most pronounced in the case of GPs. In addition to group practices, the number of MCCs has strongly increased since their introduction in 2004.

More doctors in employment relationships

Nearly half of Bavarian doctors currently work in group practices or medical care centres. The number of employment positions has risen steeply, particularly in the medical care centres. While the medical profession is increasingly becoming older, the demand for healthcare is rising as the population continues to age and to develop increasingly high standards when it comes to good healthcare provision. The social needs of the young generation of doctors, such as the increased focus of work-life balance and reconciling work and family life, especially against the background of more doctors being women, call for changes in the structure of medical care. In rural areas, these criteria are even more important because of the general shortage of doctors. The constantly increasing cost pressure in healthcare is also encouraging doctors to form cost-saving alliances.

The Medical Care Centre as an alternative practice structure

In view of the above, the MCC represents an interesting alternative practice structure, both for group practices and for single-handed practices with employed doctors. When the SHI Healthcare Promotion Act came into force in 2015, conditions in SHI-accredited physician healthcare were made more flexible. The MCC no longer needs to provide multidisciplinary medical services; it is now permissible for an MCC to only provide GP services, for example. ‘Mini’ MCCs with only one SHI-accredited position are now just as entitled to operate MCCs as alliance groups. This is of interest when no successor can be found for a practice in a rural area [13]. If medical practices are to be incorporated into a medical care centre, the acquiring doctor faces the question of whether this will trigger taxation of ‘hidden reserves’. Hidden reserves are generally the difference between the actual market value of the asset and its carrying amount under tax law. In this respect, it must be assessed whether it is actually possible to acquire the practice at tax carrying amounts in a tax-free way.

Sales and profits are not automatically tax-free

The acquisition must be considered above all in the context of the legal form of the MCC - generally a partnership organised under the German Civil Code (GbR) or a private limited liability company (GmbH). Even though the contribution of a medical practice into a GmbH may fail because of the barriers of professional and licensure law in individual cases, the reorganisation tax law at least provides for solutions in both cases that enable a tax-neutral acquisition. Nevertheless, these operations must be prepared and implemented with expert care, to ensure that the requirements of tax law and those of professional and licensure law are fulfilled.

Statis e.V.

Once a year, Statis e.V. (registered association) compiles its updated Clinic MCC company comparison. It covers 16 business key figures. Particular highly specific key figures are also available for over 20 disciplines, which makes the Statis e.V. company comparison unique. While in the previous year the profit margin Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortization (EBITDA) was slightly negative with an average of -2.7%, the corresponding value of the latest company comparison was just in the positive range, with an average of +2.5%. After taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBT), the result was, however, distinctly negative on average. The figures continue to show severe fluctuations: high six-figure annual net profits occur in some establishments alongside equally high losses in other clinic MCCs. As a general business rule, doctors’ salaries in a clinic MCC should not exceed half of the revenue. The Statis e.V. company comparison does not contain a single MCC that is operated profitably with a total expense ratio for the medical service above 48% of the MCC’s revenue [14].

The Healthcare Structure Act (GKV-VSG)

Thanks to the GKV-VSG, an MCC with only one type of specialist group is now a possibility. However, the well-established group practice must not be allowed to fade into obscurity. The group practice is a sign, however, of what patients have been criticising increasingly in recent times: the close doctor-patient relationship is suffering because the medical profession has an increasingly economic focus. In this context, it makes sense to shed some light on the advantages of a group practice (BAG) [14].

Personal character

The BAG generally comprises two or three doctors, sometimes supported by employed doctors. It is mandated by law that all names of the shareholders are displayed on the practice sign. As the entity is small, unlike an MCC, and patients are often clearly assigned to one particular doctor, patients feel that their treatment has priority and the aim is more than just profitably running a complex ‘MCC construct’.

No additional tax load

If the shareholders in a BAG employ no more than three doctors each, they are considered to still be freelancers for tax purposes and are thus not subject to business tax. Business tax can be a significant additional financial load depending on the location of the practice, as some municipalities have a high assessment rate. MCCs, on the other hand, are normally subject to business tax.

Securing of licence

Joining an MCC means entering into a close relationship, as the contributed licence is transferred to the MCC. Different rules often apply in a group practice. When a member leaves, they can take their licence with them and do not need to obtain a new one.

Economic control

As the BAG has a small number of shareholders, it is easier to keep track of the services provided by the doctors and thus to regulate the profit distribution among the shareholders fairly. While all the doctors in an MCC invoice jointly, as in a BAG, the large numbers of employees and their undoubtedly different levels of effectiveness make it more difficult to check profitability, and separate financial control is needed.

Possibility of conversion

Once a BAG has been established, this is not a one-way street: it can be converted into an MCC even years later [14].

FINANCIAL ASPECTS

Financial control

The provision of medical services in German healthcare is divided up strictly by sector. The hospitals are fundamentally responsible for inpatient treatment and the general practitioners operate in the outpatient sector. The legislature has nonetheless created a variety of ways for the hospitals to enter the outpatient sector and thus tap into new sources of income. In the context of this study, establishing a medical care centre was singled out from the wide range of outpatient options available to a hospital. From the perspective of the hospitals, the special appeal of establishing an MCC is that they function as the operator of the MCC and can thus participate in the outpatient care of patients with statutory health insurance. The question of how a hospital MCC needs to be established and run in order to be economically viable is answered in the present study on the basis of a fictitious example. The example demonstrates how the financial control of a hospital MCC can be structured in accordance with the specified goals and conditions in order to ensure that this hospital MCC is run in a commercially viable way. In a second step, the results of the completed financial control are used to show what measures need to be taken by the management board in order to maintain the stipulated profitability in the long term [15].

Important interventions for the MCC are as follows:

Ongoing consultation

Business consulting

Restructuring

MEDICAL CARE CENTRE: FINANCIAL CONTROL

Professional financial control, service management and revenue management are fundamental pillars for managing a company sustainably. Many MCCs need to catch up in this regard: the practice software is rarely able to provide reliable data. The most common problems are the depiction and monitoring of the services provided by employed doctors and the control across locations and over time. The analysis report ‘MVZ-Controlling’ (MCC Financial Control) makes service billing more focused and is geared towards the needs of multidisciplinary structures.

Services for MCC managers

Practical benefits for MCC managers

Financial control key figures from appropriate value measurement

Using the plausibility times from appropriate value measurement (EBM) and using Excel makes it possible to derive certain interesting key figures for personal practice financial control with little effort. The basic requirement is that the billed EBM items, their billing frequency, the EBM fee and the plausibility times (quarter profile) are available.

Excursion: Financial control and practice form in connection with Medical Care Centres

Figure 1 below shows the practice elements of financial control.

The charts show the subprocesses of financial control and their importance for companies, and thus also for MCCs.

Figure 2 below shows the trend for practices to take on the form of MCCs.

It is clear that there is a trend towards group practices and MCCs, namely towards larger organisational units.

Identifying time-consuming activities

To identify time-consuming activities, multiply the billing frequency and the plausibility times for all billed EBM items. This gives the amount of time invested per quarter for each item. With a little technical aptitude, an additional column can be created that shows how many items are needed to cover 80% of the theoretical KV working time. This reveals where time-consuming activities are hiding.

Checking profitability of individual services

If you multiply the time required per quarter by the personal hourly rate for each figure, the result is the doctor costs per item. If you compare this value with the EBM fee, it is clear that the difference needs to cover the practice infrastructure and its entrepreneurial profit, otherwise the provision of this EBM item is unprofitable in business terms.

Identifying the hourly rates

Viewing the EBM fee and the plausibility time in relation to each other makes it possible to identify the hourly rate achieved with each individual EBM item. This quickly reveals which services and items the practice can earn the most money with and which services yield meagre earnings.

If you are willing to make the effort and set your own time specifications for the main items rather than using the EBM time specifications (which are only meant to serve as a guide), you can further increase the potential of the information to improve business [17].

Advertising in accordance with the new SHI-accredited doctor law

The liberalisation of medical professional law and SHI-accredited doctor law is creating entirely new forms of collaboration. Shared practices, for example, can outwardly take the form of ‘medical centres’ or ‘health centres’. A group practice (with multiple disciplines or focal points) can in principle function as a medical care centre (if certain requirements are met). The boundaries between the various forms of medical collaboration are thus largely becoming blurred. This begs the question of what name can be used to describe the medical work or collaboration if the medical practice or care centre is to be named correctly in accordance with medical professional law.

Advertising with known medical partners

The new forms of collaboration (such as the partial group practice or collaborations spanning multiple locations) may, for example, lead to a renaissance of the legal form of the registered partnership, which provides for the possibility of continuing to use the names of partners who have left in the partnership name [18]. However, medical professional law specifically prohibits the continued use of the name of a partner who is no longer working, who has left or who has died (section 18a of the Medical Association’s Professional Code of Conduct (BO-Ä), Bavaria). The North Rhine-Westphalia Higher Administrative Court, for example, has made a decision in this regard [19]. Following this decision, using the name of a former practice owner on the practice sign of a group medical practice was prohibited, as this person is no longer involved in the practice’s day-to-day medical work. This means that it is no longer possible to make use of the former practice owner’s good reputation, as the function of the practice sign is to provide clear and unmistakable information regarding the doctors who actually work in the group practice. If this is not the case, this may constitute misleading advertising and an incorrect representation of professional collaboration [20].

Evocative advertising

The use of ‘evocative advertising’, which aims to evoke a particular impression, is also prohibited. Almost every week, the newspapers contain adverts for practices being closed or transferred, a practice owner being absent or ill, a practice relocating or changes being made to the consultation hours. Doctors must be aware that not all advertising is prohibited, but only advertising that does not provide information that is appropriate and in the interests of those it is aimed at. The North Rhine-Westphalia Healthcare Profession Court decided on such a case [19]. The facts of the case are as follows: an ophthalmologist advertised with the claim ‘opening of a new surgical ophthalmology department’ although the surgical services were in reality performed on the practice premises of another surgeon.

The court found two aspects of this advert to be impermissible

First, it gives the impression that surgical services are performed in the ophthalmologist’s practice. This was simply wrong. An advertisement of this type is misleading per se.

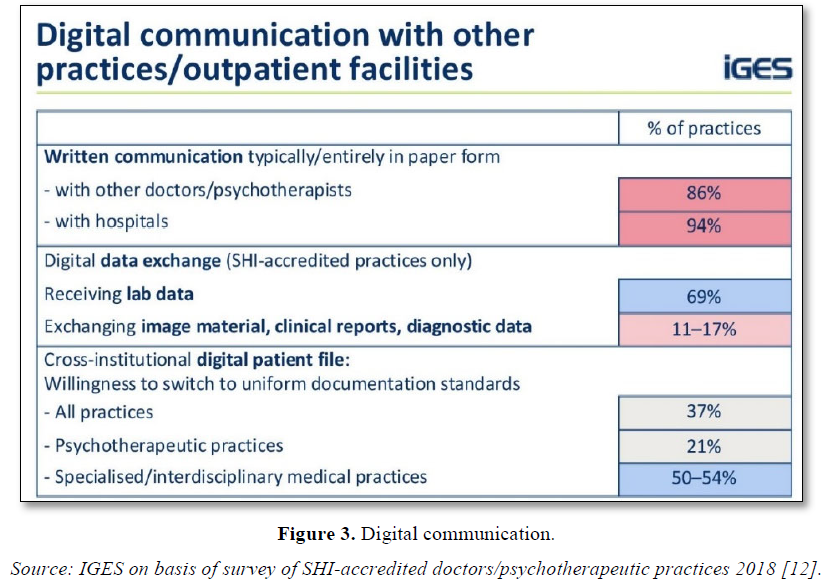

Figure 3 below shows the digital communication in outpatient facilities.

Figure 3 shows that digital data exchange is used for lab data in particular. Specialised/interdisciplinary medical practices have already switched to digital patient files in 50-54% of cases. This is undoubtedly the case on a similar scale for the MCCs in Germany.

METHODOLOGY/LEGAL BASES OF MARKETING

‘The ban on advertising serves to protect the population. It aims to uphold patients’ confidence that the doctor is not performing certain examinations, recommending treatment or prescribing medicine in the pursuit of commercial gain. The medical profession should not be based on criteria of financial success but on medical necessity.’ This was declared by the Federal Constitutional Court on 23 July 2001 [21]. Fundamentally, however, any restriction to ‘doctor’s advertising’ interferes with the freedom to pursue an occupation, as provided for by Article 12 of the German constitution. These restrictions are only justifiable in relation to specific ‘public welfare concerns’. Protection of the patient is a public welfare concern – but the patient’s interest in receiving information must also be taken into account. The case law gives precedence to the patient’s need for information.

Key activities

Under the Professional Code of Conduct, all advertising media such as the practice sign, letterheads, prescription forms, online presentations and adverts are treated equally. Radio and television advertising are also fundamentally permitted. One particularly important point is that doctors can specify key activities in all media in addition to their training and additional titles, such as acupuncture or support for people giving up smoking. There must, however, be no risk of confusion with a different type of specialist doctor or another additional title.

Unprofessional advertising prohibited

Doctors are permitted to use factual information that is related to the profession. On the other hand, advertising that is ‘unprofessional’ is forbidden. This includes laudatory, misleading and comparative advertising, for example.

Laudatory advertising

‘Laudatory’ advertising refers to advertising that is exaggerated and uses sensational and brash means. Even advertising that provides information that is of no use to the patient or that has no verifiable content can be classified as laudatory.

Misleading advertising

‘Misleading’ advertising is advertising that is able to elicit misconceptions in potential patients that are of considerable significance when it comes to choosing a doctor. Even claiming to have a unique feature can be classed as misleading (for example chirurgiepraxis-koeln.de). It is also misleading to highlight fabricated qualifications that are not based on any increase in performance or knowledge compared with the qualifications governed by the regulation on further education (such as ‘Practice for health promotion’) [22].

Comparative advertising

Comparative advertising is prohibited both in its negative form (making patients think badly of other doctors) and its positive form (using the advantages of other doctors to your own advantage).

The categories ‘laudatory’, ‘misleading’ and ‘comparative’ are merely a few examples of unprofessional advertising. The following are also prohibited:

The following are allowed, however:

If the advertising does not relate to the medical practice, but instead to a specific medical procedure, the provisions of the Act on Advertising in the Healthcare Sector (Heilmittelwerbegesetz) apply in addition to the Professional Code of Conduct. Accordingly, the following must not be used for advertising for medicines, procedures or treatments outside of specialist circles:

The above depiction is an overview of the legal bases that doctors need to observe in relation to marketing [22].

Doctors are free to use any media: practice sign, letterheads, prescription forms, online presentations and adverts. Radio and television advertising are also fundamentally permitted.

RESULTS/‘OBJECTS OF DESIRE’: MEDICAL CARE CENTRES AS A TARGET FOR SPECULATORS - GOOD RETURNS INSTEAD OF GOOD PATIENT CARE?

Private investors are evidently increasingly interested in medical care centres (MCCs), with a view to using them for speculative trading. Thus far, policy-makers seem to have little idea how to respond to this development. The Left Party parliamentary group in the Bundestag recently asked a parliamentary question on the topic. The fear is that non-medical investors would be more concerned about returns than about healthcare provision.

Because of at least two loopholes, barely anything has actually changed in practice. Private equity companies continue to invest unabated in medical care centres. The background to the question is a study produced by the services trade union verdi [23]. This study shows that although the federal government attempted to exclude non-medical investors from establishing MCCs with the 2011 Healthcare Structure Act (GKV-VSG), investors have evidently found ways around this. Private equity companies continue to invest unabated in medical care centres.

Buying hospitals - and the Medical Care Centres as well

One trick investors have used is to buy hospitals with existing MCCs and to use this workaround to become an MCC operator. The study lists a total of 11 hospital purchases that have led to the takeover of MCCs. One example: ‘In late 2015, Quadriga Capital (Frankfurt/M.) simultaneously took over the hospital Kaiserin-Auguste-Victoria-Krankenhaus Ehringshausen (Hessen) and the dental outpatient clinic Dr Eichenseer MVZ II GmbH (Munich)’ according to the ver.di study. ‘100% of the shares of the MCC GmbH were then transferred to the hospital GmbH, making the hospital the operating company of 11 MCCs in Hessen, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg’.

Or the investors can make what is referred to as an ‘asset deal’. This means that they buy the practice building, the patient records, the computers, etc. – that is, the assets. What is left behind is the empty shell of a medical registered partnership, GbR or GmbH. The previous owners become employed doctors and transfer a portion of their profit to the investors via a profit transfer agreement. On the basis of information from the Federal Cartel Office, the ver.di study cites a total of 11 financial investors owning over 200 MCCs. However, the ‘miscellaneous operators’, alongside the doctor and hospital operators, are not differentiated further in the statistics of the National Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Doctors and Dentists. It is therefore ‘not possible to achieve an overview without investigating each of the roughly 2,400 MCCs individually’. The question posed by the Left Party has now shown that the federal government evidently does not have complete figures either. According to the answer given to the parliamentary question, the number of MCCs increased from 665 to 2,821 between 2005 and 2017. Of these, 1,169 were healthcare MCCs operated by hospitals, and 1,246 were operated by SHI-accredited doctors. The federal government does not, however, know ‘how many MCCs were set up by privatised hospitals and are thus potential investment properties for corporations’ according to the Left Party parliamentary group. ‘It is estimated that roughly 420 MCCs are currently in the hands of private equity companies and asset managers,’ according to Rudolf Henke (CDU), Deputy Chair of the Bundestag Health Committee, speaking at the general meeting of Germany’s Association of General Practitioners (NAV-Virchowbund) [24].

Participating in Medical Care Centres via dental practices

When investors and practice owners come together, there is a clash between two opposing perspectives. To state the issue in somewhat exaggerated terms: dentists generally love their job and enjoy what they do for a living. They measure their success by patient satisfaction, as this is the basic requirement for recommendations, financial security and growth. Investors love returns. They have a rather distanced view of dental practices, seeing them more as an investment opportunity. They invest in practices in order to achieve high short-term returns or a good selling price later on. Both perspectives can lead to success, in entirely different ways. It is therefore essential for dentists to be aware of the motives and methods of investors so that they can define their own position better. The term ‘investors’ normally refers to a group of natural persons or legal entities investing money in dental practices. The money of this type of group is often collected in investment funds. Professional management companies search for suitable investment opportunities that they hope will provide the desired returns. On behalf of the investors, this company acquires a hospital that participates in statutory health insurance care. According to section 95 of the German Social Welfare Code, Book Five (SGB V), the hospital may participate in a medical or dental MCC or operate one. Dentists often participate in MCC GmbHs operated by hospitals without a controlling influence [25].

CONCLUSION

Over recent years, doctors in Germany have increasingly been favouring structures larger than the single-handed practice. This is the result of the cost pressure in the medical sector. In this context, the structure of the MCC is developing a central significance. The flexible organisation possibilities in these types of entities are highly appealing to doctors, especially those who are young. On the other hand, because of the potential returns they can offer, MCCs are increasingly attracting the attention of financial investors. Policy-makers have an obligation to intervene and regulate in this regard. While the MCCs should be promoted and be appealing, the positive synergy effects that these entities are evidently based on ought not lead to them drifting away from their purpose to provide quality healthcare. While this may sound simple, there are limits to how well this can be implemented in reality. As the economic policy of the Federal Republic of Germany is underpinned by the principles of the social market economy, it is clear that MCCs are affected by business principles, and much more so than group practices – even if only the options for advertising and marketing are taken into consideration. What was only of marginal relevance in the medical sector is now being exploited by modernisation processes and by MCCs in a way that calls for constant adjustment on the basis of new laws, observance of the market and a broad legal debate. All of the processes described are, of course, fully underway and of great significance in connection with Covid-19.

REFERENCES

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :