-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

David Morton, Johanna Pliske, Fabian Renger* and Milan Luliak

Corresponding Author: Fabian Renger, St. Elisabeth-University Bratislava, Slovakia.

Received: May 26, 2025 ; Revised: June 03, 2025 ; Accepted: June 06, 2025 ; Available Online: June 11, 2025

Citation: Morton D, Pliske J, Renger F & Luliak M. (2025) What is Chiropractic? A Narrative Review and Perspective from the Public Health Model. J Nurs Midwifery Res, 4(1): 1-9.

Copyrights: ©2025 Morton D, Pliske J, Renger F & Luliak M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

This review examines the development, public perception, and clinical effectiveness of chiropractic care since its inception. It traces the evolution of chiropractic from its founding beliefs to its status, which is characterized by significant internal conflict and a struggle for a unified identity within the healthcare system. It highlights the ongoing tensions resulting from differing ideological perspectives among practitioners, as well as the challenges posed by scientific oversight in establishing legitimacy. It further offers a perspective on how a self-image created by necessity and efficacy may shape an identity that best serves the public and the profession. We found clear indications that patients seek chiropractic care primarily for musculoskeletal problems, mainly back and neck pain, which is consistent with the profession's core competencies. A review of clinical effectiveness demonstrates that chiropractic interventions are beneficial for these conditions, while broader claims of efficacy remain inadequately supported. Our hope is for a chiropractic identity that recognizes its roots and the possibility of positive clinical expression outside of spinal issues, yet maintains a focus of treatment on relevant problems for which it can make the most valuable, innovative, and needed contributions. We emphasize the necessity to overcome ideological divides by working together across diverse perspectives to enhance the profession's integration into the healthcare landscape, ultimately improving patient outcomes and addressing the most significant health problems worldwide.

Keywords: Clinical effectiveness, Healthcare system, Efficacy, Spinal issues, Chiropractic care, Chiropractic interventions

HISTORY

The chiropractic profession was founded in 1895 by D.D. Palmer. At that time, he interpreted an intuitive manual correction of the spine, during which, according to lore, his patient's loss of hearing returned, providing a basis for a completely new understanding of health. Palmer's findings indicated that displaced segments of the spine could exert a detrimental effect on the spinal canal and the nervous system, potentially causing various illnesses [1]. Irrespective of the veracity of this occurrence, the notion that the spine serves as the fundamental component of well-being and that the nervous system constitutes the seat of health appeared to resonate [2]. The commercial success of Palmer's therapeutic practices led to an influx of patients and students, contributing to the growth and expansion of his enterprise. The great ambitions that this entailed were passed on to his son, Bartlett Joshua Palmer, who took over his father's school in 1906 and, with the help of targeted marketing strategies, turned it into a thriving institution. By 1925, over 80 schools had been established in North America, gradually establishing the term "chiropractic” as a permanent concept [3]. This newly developed healing art employed its own set of specialized terms, with the notion of "innate intelligence" serving as the fundamental principle or energy that facilitates healing. "Subluxation" was identified as the disruptive factor that hinders this process, and the specific adjustment of the spine by a chiropractor was designated as the corrective intervention [4]. Furthermore, the narrative incorporated mystical and religious influences, elevating chiropractic from a mere therapeutic practice to a philosophical stance on life, encompassing profound existential inquiries such as "What is life and death?" [5,6].

B.J. Palmer is widely recognized as the main pioneering figure in the field of chiropractic development. He is particularly renowned for his contributions, which include conceptualization and the establishment of the field's theoretical framework. He employed a range of diagnostic techniques, encompassing physical examination methods, X-rays, and ominous devices [7]. Despite Palmer's considerable endeavors, his use of immature approaches, in conjunction with his ambitious marketing strategies, invariably gave rise to contentions between him and the regulated domains of medicine [8]. Moreover, these disputes frequently manifested among his students, thereby giving rise to schisms within the chiropractic community over the years [9,10].

PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY

From this point forward, one of the most significant challenges confronting the chiropractic profession has persisted, and it has simultaneously served as a prerequisite for acceptance and meaningful integration into the healthcare system. The ability to define its own role and identity in modern times remains a challenge [11,12]. The origin of chiropractic is still the subject of considerable controversy [13]. Despite this, it has a profound influence on some methodologies and perspectives of individual practitioners and entire institutions, standing in stark contrast to the prevailing findings in anatomy and physiology, which are also strongly endorsed [14,15]. The considerable disparity between tradition and the cult of personality surrounding Palmer, in conjunction with the contemporary findings in neurology, biomechanics, and basic anatomy, engenders substantial disagreement, uncertainty, and even conflict [16]. This substantial obstacle hinders the establishment of legitimate standards [17]. This phenomenon can manifest during the early years of chiropractic students' education and training. Students' attitudes toward chiropractic professional practice appear to be influenced by a combination of progressive and regressive ideological perspectives. These attitudes are characterized by complex patterns of conflicting responses, which are evident within and across various statements of identity, roles, settings, and the future [18,19]. As might be anticipated, this early intra-professional discourse persists among chiropractors in the field. In Europe, there is considerable variation in the manner in which health care is delivered. This variation is evident in the frequency of visits to healthcare providers, the way diagnoses are made, and the extent to which patients are educated on significant health issues, such as vaccinations [20]. A parallel can be drawn between the present situation in the United States and the aforementioned circumstances.

The clinical ideology, beliefs, and practices of chiropractors vary according to geographic region, type of chiropractic program attended, and the years since completion of their chiropractic degree [21,22]. It is challenging to reduce the variability of professional attitudes to a manageable extent. A variety of studies have employed typification, utilizing designations such as "subluxation-based" and "musculoskeletal" or "orthodox and unorthodox" [23,24]. However, the methods of operation and thought reflect a strong individualism, which underscores the heterogeneity that can ultimately result in divergent public health messaging and, consequently, public confusion [25]. This issue has previously been addressed through the establishment of accreditation societies that collaborate closely with legislative decision-makers. For instance, the Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE)-USA has numerous regional partners, including the European Council on Chiropractic Education (ECCE) and the CCE-A in Australia. The objective of this initiative is to establish a global interface between governments, educational institutions, the public, and chiropractors, with the subsequent aim of unifying these entities on a global scale [26]. Despite the encouraging nature of this approach, its implementation has exacerbated existing internal and external conflicts within the profession rather than fostering unity. There is a pervasive concern that the established standards and the individuals responsible for their development do not adequately address the conflicting interests between higher authorities and the concerns and aspirations of clinicians. This perceived discord results in a sense of oppression, which subsequently fosters rejection [27]. Within the public health model, identity can be defined by public need, perception, knowledge, and effectiveness [28-30]. It is hypothesized that this approach could allow for a preliminary attempt to address the significant division within the chiropractic profession, define the beginnings of an identity, and facilitate a useful integration into the healthcare system.

PUBLIC PERCEPTION

The importance of public education and the cultivation of a comprehensive understanding of health issues and interventions cannot be overstated [31,32]. However, it is imperative to distinguish between education and re-education, as the terms are not synonymous. Most patients enter the practice with a well-defined objective. It is imperative to acknowledge and embrace this understanding as a preliminary and essential step in fostering an identity that is aligned with social perceptions. The body of research on this topic is limited, but some studies have offered valuable insights. In Victoria, Australia, the Chiropractic Observation and Analysis Study (COAST) was conducted to ascertain patients' intentions. This study involved the meticulous documentation of 100 patient encounters, each selected from a total of 180 chiropractors who were randomly recruited for the study. The analysis indicated that the majority of patients sought treatment for musculoskeletal reasons, although, a negligible proportion of patients indicated that they were consulting for psychological or digestive problems [33]. In the province of Ontario, a study with a comparable methodological approach was conducted to investigate the utilization of chiropractic care. The primary reasons patients visited chiropractors were observed and recorded in accordance with the diagnoses made. Musculoskeletal problems were identified as the most significant health concern, and pain and neck pain were particularly salient [34]. Research from South Africa on chiropractors found results consistent with those previously mentioned. The data from over 600 chiropractors were collected. The study concluded that the most common patient presentation was chronic musculoskeletal pain, particularly low back pain. The research also provided insights into types of treatment and diagnoses [35]. In the United States, the founding country of chiropractic and its philosophical approaches, back problems are also gaining ground as the most important part of the public perception [36]. Additional articles on utilization rates, reasons for utilization, and demographic characteristics of chiropractic patients were reviewed in other research. A total of 85 individual studies demonstrated that patients sought chiropractic care for back- or neck-related issues. Furthermore, chiropractors were consulted for the treatment of extremity problems. The treatment of other conditions could not be significantly determined [37]. In the domain of chiropractic, the notion of inducing comprehensive processes through spinal adjustment has persisted, with the assertion that it exerts a favorable influence on a wide range of clinical manifestations [38,39]. Despite the fervent advocacy for this self-image, its expression is only superficially mirrored by public perceptions and clinical interactions with patients. Research on the subject indicates that no large-scale study of the chiropractic sector has demonstrated more than subtle tendencies in other directions than musculoskeletal complaints as the primary focus of patients when they elect to consult a chiropractor; thus, the public's understanding of the role of a chiropractor is well-defined, and there is a sense of assurance in the competence of chiropractors within this established framework.

EFFICACY

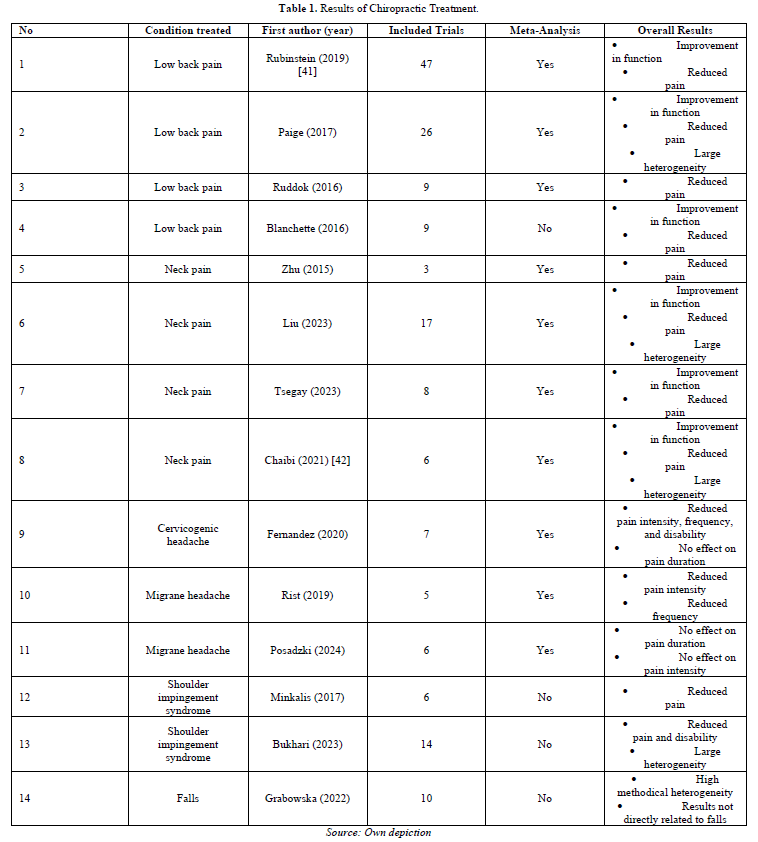

In light of the public's perception of chiropractors as specialists in back, neck, and skeletal pain, it is imperative to determine the validity of this professional designation in terms of its practical effectiveness. Specifically, it is necessary to ascertain whether there is a discrepancy between the public's perception of chiropractic services and the scientific consensus regarding their efficacy. To achieve this, a comprehensive literature search was conducted in the PubMed and Dimensions databases. This investigation focused on systematic reviews, with the aim of determining the effectiveness of chiropractic and spinal manipulation in the context of the most significant and stressful forms of illness that currently exist. The following criteria were established for the determination of eligibility: Studies must have been published no more than ten years prior to the present date, and they must have focused on high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) techniques as a therapeutic modality. Consequently, spinal manipulation and chiropractic served as search terms, each combined with one of the 25 most prevalent clinical pictures for years lived with disability [40]. Manual therapy, osteopathy, and related terms were excluded due to the broad spectrum of approaches they encompass. The results of the studies documented in the included reviews indicate that low back and neck pain are at the core of chiropractic practice. The evidence in these areas is sufficiently comprehensive and strong to allow cautious conclusions to be drawn about the potential beneficial effects of chiropractic care. Efficacy has been demonstrated by the reduction of pain and improvement of function in patients who have undergone the procedure. The prevalence of satisfactory responses to headache disorders and other skeletal disorders has been documented, although the evidence for these observations is less conclusive. The outcomes associated with these conditions are characterized by a greater degree of heterogeneity than those observed for back problems. A review was conducted to analyze the effects of chiropractic care on the incidence of falls. The analysis was primarily concerned with factors that have purely hypothetical effects on the frequency and severity of falls (Table 1).

RESEARCH AND SPECIFICITY

Specializing in an area that is already widely treated could lead to a loss of autonomy and independence; in fact, it could result in a loss of identity. However, back pain is a health problem that still represents an immense burden for the healthcare system and the public, and it encompasses many different clinical pictures and functional disorders, all of which leave sufficient room for specialists to improve the situation. Gradually moving away from the historical model of subluxation [43], the concept of spinal dysfunction and the integration of the associated dysfunctional afferents into the brain increasingly forms the basis of thinking and research in this field [44,45]. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and electromyography [46,47] provide deeper insights into the functioning of spinal manipulation and its effects on the interaction between the joints and the neuroregulatory processes that stabilize them. Neurological diagnostics have repeatedly shown the direct influence of spinal manipulation on brain function [48]. These and other findings have led to the view that the spine is an integrative structure that, through high-speed, low-amplitude manipulations, triggers sensory and motor activities in specific areas of the brain that have distinguishing effects from other therapies and serve a different mechanism of the overall problem [49]. Although the tangible, clinical characteristics of spinal dysfunction have been discussed in the literature, they still leave much room for further research. Some phenomena can be observed after spinal manipulation that are, at first glance, quite unique. Significant increases in proprioceptive accuracy have been observed with chiropractic treatment [50]. Other studies have indicated shorter reaction times and a better sense of balance [51]. In addition, the maximum strength of various muscle groups and their endurance has been shown to increase significantly [52]. These various observations may appear to be a kind of clinical gimmick, but they become a central component of the special nature of chiropractic when one considers the fact that the subjects in the studies described suffered from recurrent subclinical complaints of the back and neck. This, in parallel to the improvement in the parameters described, was significantly reduced in frequency and intensity. These effects seemed to be absent or drastically reduced in healthy subjects after spinal manipulation [53], emphasizing the relationship between spinal dysfunction, pain, and neurological function parameters.

Investigations of these connections have shaped the most accurate understanding of modern chiropractic to date. According to this model, spinal dysfunction or the "subluxation complex" begins with an initial trauma that causes a permanent contraction mechanism of the paraspinal muscles via nociceptive activity. This contraction continues in part even after the actual pain stimuli have subsided and is adapted by the neuroregulatory mechanisms of the region [54]. A permanent error that disrupts the synchronization between current proprioceptive feedback develops and consolidates until it is professionally corrected [55]. Coordination of complex movements becomes reduced and reflex stabilization of the spine is slowed, making re-traumatization likely. Consequences include recurring pain symptoms due to marginal stress, scar formation, and/or early joint degeneration.

INTEGRATION AND SYMBIOSIS

Health care and therapy must adapt to societal needs in order to establish their identity. Failure to follow this path, or to pay sufficient attention to it, leads to ongoing internal and interdisciplinary conflicts that can paralyze progress or even extinguish an emerging profession. Chiropractic is a prime example [56]. A closer analysis of the circumstances reveals that there is public demand [57]. Not only has chiropractic been around for a long time and is well known in common parlance, but the presence and number of patients seeking the help of a chiropractor is growing [58]. Patients, legislators, and payers alike benefit from a popular approach that helps alleviate a significant burden on the healthcare system [30,29]. In addition, certain clinical successes of chiropractic cannot be denied, which is a strong basis for a healthy self-image. However, the justification for chiropractic's existence as an independent profession becomes debatable when it comes to its specificity [59]. An identity can also fail if there is no exclusivity in diagnosis, therapy, or way of thinking [60]. This may be one reason why some chiropractors cling so tightly to historical concepts. Considering recent findings on the effects of spinal manipulation on neuro skeletal mechanisms, this is rather unnecessary. The body of evidence describing the autonomic regulatory processes of the spine in relation to the central nervous system, as well as the associated dysfunctions, continues to grow [52,61,62]. While there is certainly much room for new knowledge and certainty, there is also much opportunity to apply the knowledge gained to improve the situation of many. A definitive classification of back and neck pain is still lacking, and treatment is often inefficient [63]. A profession that seeks to position itself clearly within this field to offer the most effective approaches to patients is certainly welcomed by all stakeholders. The internal conflicts, some of which are ideological, remain unresolved. It will certainly not be possible to completely unite the vitalist and mechanistic camps without compromises [56]. Nevertheless, there are ways to form an intersection. Although some views are without reason, it is precisely these views that I strengthen through strong opposition. The approach should, therefore, not be to work with exclusion, prohibition, or even defamation, but rather to examine such views for their integrable elements. Palmer's original thinking, on which traditionalists rely so heavily, did not speak of healing, but of reducing "dis-ease," a state of impaired overall function [64]. According to the available evidence, chiropractic has the greatest effect for and on people with recurrent back or neck pain but can also lead to improvements in other physical parameters [51,65]. Those portions of clinical benefit that are reproducible and necessary, such as the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, should always be considered the core of the work for ethical and public health reasons [66]. At the same time, however, they could be an indicator that effects beyond symptomatic improvement may be possible for those involved. At this point, the mechanistic group of the chiropractic society should allow for justification of the unknown. Science strives to understand and categorize every aspect of a treatment but sometimes tends to overlook the fact that this is not always necessary if a treatment is essentially working [67-70]. Unknown phenomena are not only the subject of its researchers, but the very foundation of the scientific spirit. This perspective provides symbiotic benefits when both extremes cooperate. Recurrent pain can be seen as the most important expression of Palmer`s “dis-ease” and the parameter for multi-phenomenal effects of chiropractic on a person [71-74]. Openness to unexpected or less researched observations into the research process provides room for new insights, which may be incorporated in various ways [75-77].

CONCLUSION

Soon after its founding, tensions and conflicts developed within the chiropractic community, which continue to impede the integration, growth, and progress of the profession as a whole. The formation of a unified identity requires a self-image that is acceptable to all stakeholders. Time has proven the difficulty of creating an identity from within, given the complex history, the strong individualism that extends to a cult of personality, the increasing pressure of scientific scrutiny, and the many currents and interest groups that seek to represent chiropractic. According to the public health model, addressing the greatest needs of the population and the healthcare system, which chiropractic can potentially serve in its unique way, is an excellent starting point for building a co-created identity. Our first indication of this need was the public perception of the chiropractic profession. Patients develop their own sense of efficacy and benefit, independent of the will of the practitioner or the institutions above them. This collective feeling has been illustrated in a number of studies and shows that by far the largest percentage of chiropractic users see it as a treatment and/or prevention for back, neck, and other musculoskeletal complaints.

This public identity is supported by a significant number of systematic reviews that confirm that the primary benefits of chiropractic are in this area. We have not been able to find any significant successes of chiropractic in the context of the most important clinical pictures of our time, except in the area of musculoskeletal complaints. As public health researchers, we suggest that back and neck pain should reasonably be at the core of the chiropractic identity, especially since there is a growing body of evidence that chiropractic could serve another aspect of this immense population problem, which is a beneficial integration opportunity for all. It should be noted, however, that we understand the connection to traditional approaches, and these should also have their place, to an appropriate degree, as long as they are complementary and do not distort the overall self-image of the profession in an unrealistic way. Small shifts in perspective, such as viewing pain as an expression of the "dis-ease" described by Palmer, or incorporating unexpected treatment results into the research process, could provide both camps with a rudimentary symbiotic basis and bring about a gradual rapprochement. While it is evident what chiropractic has to offer in terms of public need, without this reconciliation and the resulting consensus, the potential for interdisciplinary work and healthy growth will never be realized.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :