-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Yoshiko Shimizu*

Corresponding Author: Yoshiko Shimizu, Nagoya University of Arts and Sciences Department of Nursing, Nagoya Gakugei University, Japan.

Received: September 23, 2023 ; Revised: September 30, 2023 ; Accepted: October 03, 2023 ; Available Online: October 16, 2023

Citation: Shimizu Y. (2023) Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale and the Relationship with Parenting Happiness, Parenting Stress, and Husband’s Parenting Behaviors. J Nurs Midwifery Res, 2(1): 1-10.

Copyrights: ©2023 Shimizu Y. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

The ideal form of co-parenting differs greatly depending on the sociocultural background and context. Therefore, we developed the Co-parenting Awareness Scale (29 items, 4 factors) based on a survey of Japanese population of some regions raising children under the age of 5 years. Furthermore, we performed an online survey in a wider region under the same conditions with ethical considerations. We conducted the main survey with 378 mothers and fathers who were willing to participate in the survey and received 334 responses.

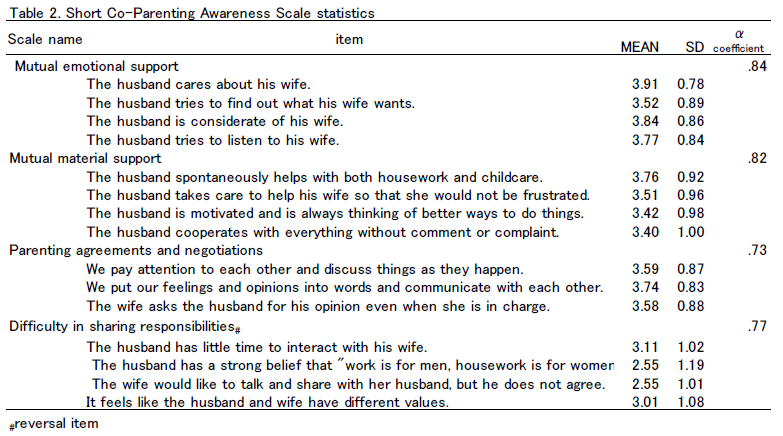

After a confirmatory factor analysis, the Co-parenting Awareness Scale had 15 items in 4 factors, and the factor names and number of items (Cronbach’s α coefficient) were as follows: “Mutual emotional support,” 4 items (0.84); “Mutual material support,” 4 items (0.82); “Parenting agreements and negotiations,” 3 items (0.73); and “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities,” 4 items (0.77), which were used to establish the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale.

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between childcare happiness and stress and husband’s parenting behaviors (50 items in housework and parenting) to highlight the benefits of the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale and co-parenting.

Higher levels of elements of childcare happiness, such as “joy of raising children” and “gratitude to my husband,” and comparatively lower levels of childcare stress, such as “childcare anxiety” and “husband’s lack of support,” were associated with good scores on the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale.

Regarding the husbands’ parenting behaviors, they were related to their perceptions, such as “I am not supportive of raising children,” “I value myself more than my children,” and “I don’t understand how difficult it is for my wife to raise children,” indicating that an increase in husband’s parenting behaviors leads to a decrease in “husband’s lack of support” and that higher childcare happiness and lower childcare stress are conducive to good co-parenting.

Keywords: Co-parenting, Short scale, Couple, Childcare happiness, Childcare stress, Childcare behavior

INTRODUCTION

Most Japanese families are nuclear, which increases the importance of cooperation between husband and wife in child rearing. In addition, the number of consultations about child abuse is increasing [1], and mothers are burdened with the responsibility of parenting, which led us to propose an intervention plan to promote effective co-parenting to support new parents. In particular, initiatives that focus on co-parenting during the post-partum period have not been sufficiently implemented in Japan; thus, this is a unique initiative. We believe that this initiative will help address various problems faced by postpartum couples today, such as divorce during the early child-rearing period, postpartum crisis, and abuse. By engaging in parenting together as a couple and reassessing the relationship between the husband and wife in association with their children, it is expected that both partners will gain confidence as parents, mature as individuals, and exert a positive impact on the child’s environment as they grow up. We believe that support in the foundation of new families is a resource that must be worked on in the future and is therefore a meaningful topic of research.

What is important is that both parents agree with and assure one another that their roles and responsibilities are fair. Successful co-parenting has been found to improve couples’ relationship with each other, reduce childcare anxiety and stress, enhance the quality of parenting and parents’ kindness toward their children, and build positive relationships that promote children’s development [2-4]. However, while the importance of support for co-parenting has been identified, this study aimed to propose an intervention program to boost co-parenting. A set of appropriate evaluation criteria is needed for this initiative; thus, we are currently using such a scale to explore factors related to co-parenting. Therefore, we conducted interviews with Japanese couples in the midst of parenting to develop the Co-parenting Awareness Scale [5,6]. Subsequently, the items were tested to determine if they measured the concepts as expected, which led to the development of the 4-factor, 15-item Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale comprising 4 items in “Mutual material support,” 4 in “Mutual emotional support,” 3 in “Parenting agreements and negotiations,” and 4 in “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities (reverse-scored items)” [7]. Higher scores in the subscales “Mutual material support,” “Mutual emotional support,” and “Parenting agreements and negotiations” and lower scores in “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities” indicate better co-parenting awareness.

The Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale is significantly associated with parenting time, number of children, age of children, and discussions about division of parenting roles before birth. Couples where the husband engaged in more hours of childcare performed better in all four subscales of the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale. Families with younger children scored better in “Mutual material support,” “Mutual emotional support,” and “Parenting agreements and negotiations,” whereas “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities” worsened as the children grew older. It was suggested that husbands are expected to take a proactive part in parenting by discussing key aspects based on the age of the child and the division of parenting roles from the time of pregnancy and by using the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale to become conscious and active participants in cooperative co-parenting.

Although Japanese men are spending more time in parenting duties, a remarkable gender gap remains in the division of roles by gender, such that the hours women spend in parenting are increasing [8]. While parenting is often done in cooperation, there remain questions, including whether co-parenting is affected by the parents’ childcare happiness and stress and details of parenting. In particular, the effects of childcare happiness and stress on the relationship between children and between parents are evident [9,10], and cross-cultural studies have shown that Japanese fathers prioritize work and the Japanese culture accepts this prioritization [11]. Therefore, it is expected that Japan has various unique problems and challenges related to co-parenting. This study hypothesizes that higher levels of childcare happiness and lower levels of childcare stress will result in favorable co-parenting and husband’s parenting behavioral outcomes.

This study reports the results of the analysis of childcare happiness and stress and husband’s parenting behaviors (50 childcare items), which were unpublished owing to the limitation of the character count of a previously published article [7].

OBJECTIVES

To examine the relationship between husband’s parenting behaviors and childcare happiness and stress using the developed Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey Methods

A questionnaire was administered via an online survey (via Freeasy, an academic and research institution).

Survey Respondents

The study targeted the prefectures with the highest number of children, namely, Aichi, Hiroshima, Saitama, Shizuoka, Chiba, Osaka, Tokyo, Fukuoka, Hyogo, and Hokkaido. The respondents were married (not widowed or divorced) fathers and mothers (aged 27-39 years) of children up to 5 years of age.

Survey Details

Preliminary Survey

The survey items confirmed whether the respondents had children up to 5 years of age, whether they were married and not widowed or divorced, the age of the children, the number of children, responses to the Co-parenting Awareness Scale, and willingness to cooperate in a future survey.

The survey was conducted on March 13, 2023. In this survey, 1,000 people (500 men, 500 women) were invited to participate and 1,000 responses (100%) were received. There were 608 valid responses (305 men, 303 women), and 378 respondents (188 men, 190 women) expressed a willingness to cooperate in a future survey. The respondents’ average age was 34.38 ± 2.94 years for men and 33.47 ± 3.09 years for women.

Main Survey

The survey was conducted between April 7 and April 20, 2023. Of those invited to participate, responses were received from 168 out of 190 women (88.4%) and 170 out of 188 men (91.0%). The survey items confirmed the presence or absence of cohabitants other than the couple and children, sleep and waking up times (≥5 days a week), whether the respondents woke up earlier than 5 AM, whether they went to bed after 12 A.M., whether they performed childcare on non-working days, and fathers’ parenting time on working and non-working days. Responses to the Childcare Happiness Short Scale, Childcare Stress Short Scale, Marriage “Reality” Scale, and Marital Communication Attitude Scale were also included.

Scales Used in the Surveys

Short Version of the Co-parenting Awareness Scale

The Co-parenting Awareness Scale [5,6] comprises 29 items based on awareness and cooperation in childcare between husband and wife, “Kindness and appreciation toward the partner,” “Desire and actions to cooperate,” “Communication between husband and wife,” and “Obstacles to co-parenting.” Its short version, the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale, comprises 15 items in 4 factors [7], namely, 4 items in “Mutual emotional support,” 4 in “Mutual material support,” 3 in “Parenting agreements and negotiations,” and 4 in “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities,” which are reverse-scored items. Each item is answered on a 5-point scale from “1. Strongly disagree” to “5. Strongly agree.” Higher scores indicate better awareness of co-parenting and better understanding of the subscales.

Short Form of Childcare Happiness Scale

After first creating a 41-item Childcare Happiness Scale [12], the Short Form of the Childcare Happiness Scale, which evaluates positive emotions that mothers feel in parenting, was used [9]. The scale comprises 15 items in 3 factors, i.e., 5 items on “the joy of raising children,” 4 on “bonding with children,” and 4 on “gratitude to my husband.” Each item on this scale of childcare happiness is answered on a 5-point scale from “1. Strongly disagree” to “5. Strongly agree,” with higher scores indicating higher levels of happiness in parenting.

Short Form of Childcare Stress Scale

The 130-item Mother’s Perception and Evaluation of the Childcare Environment [13] and the 33-item Childcare Stress Scale were examined [14]. Subsequently, the short form of the Childcare Stress Scale, which evaluates negative emotions that mothers feel during parenting, was used. The scale comprises 16 items in 3 factors, i.e., 6 items on “mental and physical fatigue,” 6 on “childcare anxiety,” and 4 on “husband’s lack of support” [10]. The items in this scale of childcare stress are answered on a 5-point scale from “1. Strongly disagree” to “5. Strongly agree,” with higher scores indicating higher levels of stress in parenting. For the purposes of this study, we focused on the subscale items related to “husband’s support.”

Analysis Methods

The results of the web survey were saved as CSV files, which were downloaded, aggregated to import into statistical analysis software, and analyzed using the statistical analysis software IBM SPSS 25 and IBM Aoms 26.

The responses for the Childcare Happiness Short Scale and Childcare stress Short Scale were compared between the husband and wife. Furthermore, the relationship between childcare items was compared based on five categories of number of items. The relationship with the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale was analyzed statistically using correlation bivariate analysis and non-parametric tests to compare the high- and low-scoring groups after a GP analysis of the scale into the two groups divided by the median as the cut-off.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The participants were informed that cooperation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study without negative consequences via a written invitation for participating in the survey. The questionnaire included a checkbox to confirm their consent. This study was reviewed by the Research Ethics committee of Nagoya University of Arts and Sciences (approval number: 621; approval date: October 28, 2022).

RESULTS

Valid responses were obtained from 334 women and men aged 33.48 ± 3.04 years and 34.61 ± 2.95 years, respectively. The sample of men included 170 workers and 0 homemakers and that of women included 94 workers and 70 homemakers. The average number of children was 1.67 ± 0.74, and the average age of children (up to 5 years of age) was 2.26 ± 1.58 years.

Childcare Happiness and Stress Status

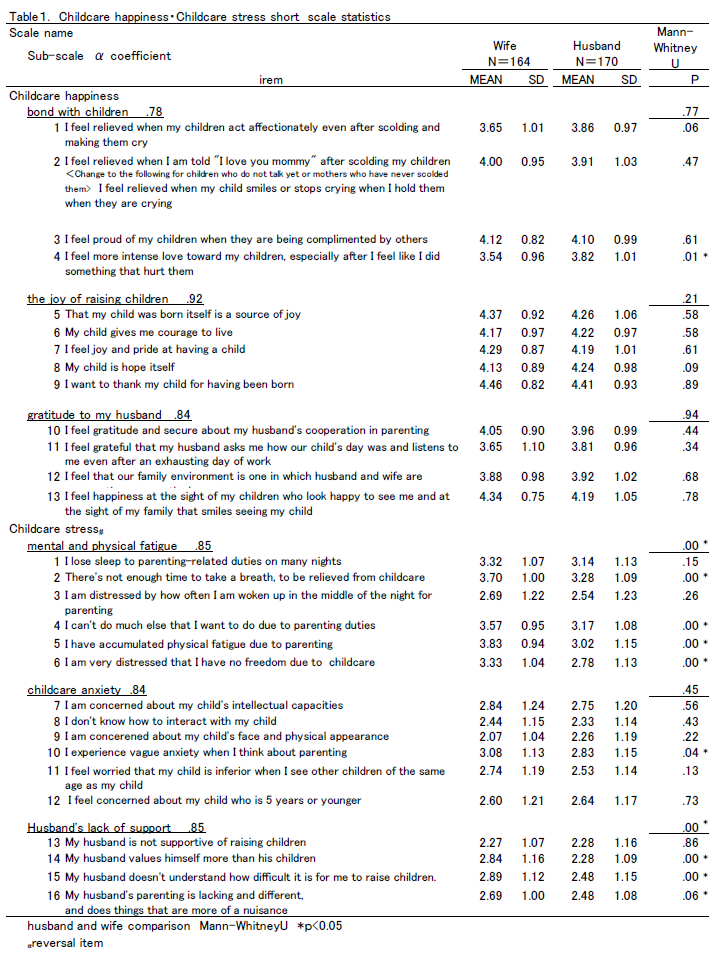

There was no difference in the results between husbands and wives in terms of childcare happiness, as assessed using the Childcare Happiness Short Scale or Childcare Stress Short Scale. However, wives scored significantly higher in two items of childcare stress, i.e., “mental and physical fatigue” and “husband’s lack of support,” indicating that wives experienced more intense childcare stress (Table 1). Mental and physical fatigue was correlated with “childcare anxiety” (R = 0.37) and “husband’s lack of support” (R = 0.31, significant at p < 0.01).

Relationship between the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale and the Childcare Happiness Short Scale and Childcare Stress Short Scale

The statistics of the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale are shown in Table 2.

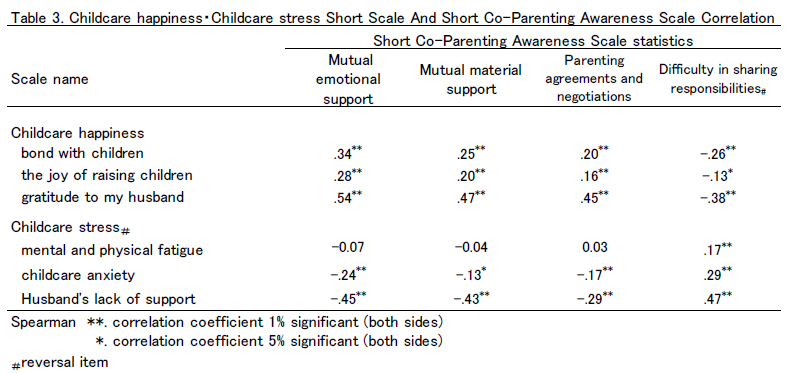

Significant positive and negative correlations were observed between the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale and the Childcare Happiness and Stress Subscales; however, “mental and physical fatigue” were unrelated to “Mutual emotional support,” “Mutual material support,” and “Parenting agreements and negotiations” (Table 3).

Regarding the relationship with the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale, high scores for childcare happiness and low scores for childcare stress were associated with high “Mutual emotional support,” “Mutual material support,” and “Parenting agreements and negotiations” and low “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities.”

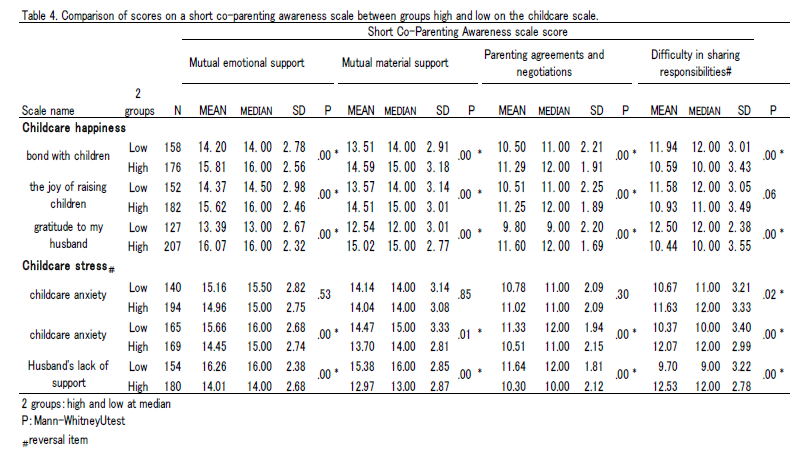

These relationships can be considered substantial. To test these relationships, the high- and low-scoring groups in the Childcare Happiness and Stress Subscales (GP analysis for the two groups was all p = 0.000 the high group was high and the low group was low) to compare the scores for the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale.

Relationships were observed between childcare happiness and all items, except “bonding with children” and “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities.” Childcare stress was associated with “Childcare anxiety” and “Husband’s lack of support,” and Mental and physical fatigue” was significantly associated exclusively with “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities” (Table 4).

Relationship between the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale and Childcare Items

State of Household Chores and Parenting Tasks Performed by the Husband

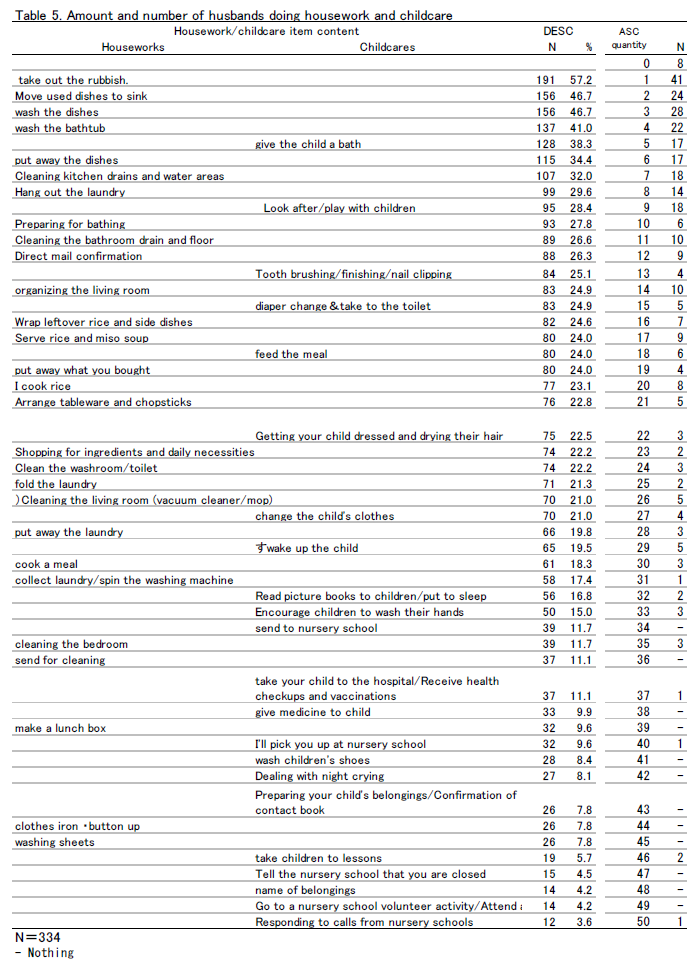

Household chores and childcare tasks that husbands perform more than or equal to their wives (selected from 50 general items) are shown in descending order, and of the selected 50 items, the number of items they perform is shown in ascending order (Table 5). The number of items was a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 50, with an average of 10.23 ± 9.6. The number of people divided into five categories based on the average number of items with 10 as a reference was 8 people for 0 items (2.4%), 205 for 1-10 items (61.4%), 72 for 11-20 items (21.6%), 35 for 21-30 items (10.5%), and 14 for ≥31 items (4.2%).

Relationship with the Husband’s Childcare Items

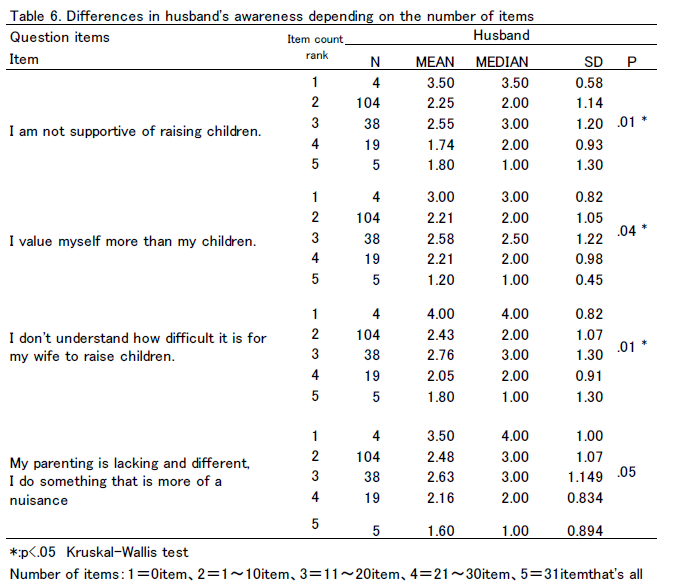

The husbands’ household chores and parenting behaviors are interpreted as their cooperation and were considered to be associated with the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale. Therefore, the significance probabilities were “Mutual emotional support,” p = 0.53; “Mutual material support,” p = 0.58; “Parenting agreements and negotiations,” p = 0.12; and “Difficulty in sharing responsibilities,” p = 0.18. These probabilities were based on the comparison of the five categories of the number of items of the four subscales for the husbands Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale. There was no significant difference in the subscale scores by number of items (quantity). Furthermore, we focused on one item from “husband’s lack of support,” i.e., “I am not supportive of raising children,” and compared the five categories of four items of husband’s lack of support as the number of childcare items. We found significant differences in the three items of “I am not supportive of raising children” (p = 0.012), “I value myself more than my children” (p = 0.035), and “I don’t understand how difficult it is for my wife to raise children” (p = 0.012) (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Relationship between Co-Parenting and Childcare Happiness and Childcare Stress

A relationship was shown between childcare happiness and childcare stress with co-parenting.

However, the wives were suffering from accumulated mental and physical fatigue, as they were physically exhausted from raising their children. The wives were unable to do other things they wanted to do because of having to care for their children and were extremely distressed by not being able to exercise their own freedom. Although an association was observed between mental and physical fatigue and the Co-parenting Awareness Scale, the vicious cycle involving mental and physical fatigue, “childcare anxiety,” and “husband’s lack of support” as mental and physical fatigue exacerbated; thus, the effects on parenting cannot be ignored.

Elements of childcare happiness, i.e., “joy of raising children” and “bonding with children,” decrease as the age of children increases, and “gratitude to my husband” also tends to decrease as the age of the youngest child increases [9]. It is important to work on improving co-parenting around the time when childcare happiness declines. Perfectionism leads to the accumulation of childcare stress [10], and aspects such as personal and other factors should be examined in addition to “husband’s lack of support.” Moreover, a relationship between good co-parenting scores and low depression scores was noted [15], which suggested the benefits of childcare happiness and mental capacity to accept childcare stress itself. Co-parenting support should be provided along with an awareness of these synergistic relationships.

Significant correlation between marital parenting and childcare happiness was observed in all items of childcare happiness, and we believe that it improves the quality of child rearing. The recognition of female parenting is a parental development consciousness, and it enhances the awareness of relationships with others. This awareness leads to good marital relationships and increases the sense of happiness in childcare [5,6].

Relationship between Co-parenting and Husband’s Child Care Items

If wives performed 50 of the items in housework and childcare list, husbands performed 1/5th of them, more than half of the husbands performed only 1 item, and only one husband performed all 50 items. Hence, it is difficult to interpret these statistics.

There was no relationship between the five categories based on number of items (quantity) and co-parenting. Also, there was no association between husband’s parenting behaviors and the subscale on “husband’s lack of support.” However, husbands with stronger subjective perceptions, such as “I am not supportive of raising children,” “I value myself more than my children,” and “I don’t understand how difficult it is for my wife to raise children,” performed significantly lower number of childcare items. Such subjective perceptions pertained to 3/4 items of “husband’s lack of support,” suggesting that performing more childcare items lowered “husband’s lack of support,” positively affecting co-parenting.

In this survey, we found that many wives wanted their husbands to assume their share of household chores, based on the question, “I want my husband to give me a sense of mental security and satisfaction rather than share the household chores.” The results also indicated that the husbands or wives who wanted a more equal division of tasks actually performed more household chores.

In the free description of their ideals of their husbands’ parenting, in addition to specific support such as wanting them to be more involved with their children on their days off, helping them get ready to go out, and asking them to put their children to bed, they also asked for caring, kindness, and emotional support, such as thinking together with them. Concerning financial support, the wives seemed to want more money to go out with their children on weekdays. Wives’ desire to have their husbands take care of them is a crucial aspect of the reality of Japanese couples raising children and can potentially become an issue in promoting co-parenting. A strong association with gender roles was observed outside Japan too. For instance, Finland, Portugal, and Japan have witnessed progress in gender equality and have egalitarian views on the sharing of parenting responsibilities between couples [11]. In a comparative report on these countries, commonalities were revealed between the three countries as well as points that were specific to Japan. The commonalities include the processes by which couples build consensus and team spirit. Finland and Portugal display ambivalent expectations in that although parenting is expected to be centered on mothers, equality is pursued and emotional support is desired. On the contrary, in Japan, it is accepted that fathers prioritize paid work.

The five factors related to the marital relationship during pregnancy are acceptance by the partner, support and trust from the husband, good interpersonal relationships, and economic and lifestyle fulfillment. Hence, apart from expectations related to childbirth and childcare, most of these factors pertain to marital trust and finances [16]. These fundamentals do not change during the parenting stage either. Furthermore, husbands who participate in parenting more frequently have been reported to experience psychological well-being [17]. This view was further supported by the findings of this study, which suggested that encouraging husbands to participate in parenting led to good co-parenting. This participation was beneficial for the husbands too as it increased “the joy of raising children” and “bonding with children” and lowered “childcare anxiety.”

A literature review on the effects of paternal participation in parenting showed that mothers felt reduced stress from parenting and had better well-being when they recognized that their husbands participated actively in parenting compared with when they did not. Furthermore, it has been suggested that mothers’ recognition of active paternal participation in parenting had positive effects on the children’s growth, health, and development, for example, by preventing injuries and overweight and obesity. However, paternal participation in parenting as evaluated by the fathers themselves may not be correlated directly with the mothers’ sense of burden. There are few studies that have examined the effects (such as on quality of life) of paternal participation in parenting on the fathers, and consistent trends were not observed [18,19]. Evaluating the beneficial effects of co-parenting on both husbands and wives, as opposed to assessing just paternal participation in parenting, is a meaningful strength of this study. Our results should be further expounded upon to develop intervention plans for promoting co-parenting as a future challenge. An intervention study through a program for couples expecting a child was conducted in Japan by the Tohoku University Co-parenting Research Team [20,21]. My challenge is a program to promote parenting for married couples during the child-rearing period.

CONCLUSION

The elements of childcare happiness “joy of raising children” and “gratitude to my husband” and elements of childcare stress “childcare anxiety” and “husband’s lack of support” were associated with all four subscales of the Short Co-parenting Awareness Scale. The husband’s parenting behaviors were not associated with co-parenting. However, performing several items of parenting and household chores lowered “husband’s lack of support” and may not be completely unrelated to co-parenting. This finding indicates that the childcare items and the increased performance in these items may improve co-parenting.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The challenge for the future is to develop and evaluate plans to promote awareness of husband-wife parenting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Crimson Interactive Pvt. Ltd. (Ulatus) - www.ulatus.jp for their assistance in manuscript translation and editing.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C “Development and Assessment of a Plan to Promote Co-parenting” [22K10939 0001] (2022-2025).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose in association with this study.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :