-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Daud N Mollel*

Corresponding Author: Daud N Mollel, Department of Business Management and Administration Studies, Faculty of Commerce and Business Studies, St. John’s University, Tanzania.

Received: February 10, 2024 ; Revised: March 18, 2024 ; Accepted: March 21, 2024 ; Available Online: April 11, 2024

Citation:

Copyrights:

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

A cross sectional survey design was employed due to its ability to explain the prevailing conditions as perceived by the respondents, the studies are carried out once at a particular point in time and is not repetitive in nature. Information was gathered from 210 respondents using a 5-point Likert scale from the list of 22 statements (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) which were assessed using mean scores, standard deviations and reliability tests and the correlation coefficients of the critical constructs were analyzed. Although Tanzania has wealth of natural and cultural heritage to provide unique experiences to tourists, most of the guiding policies are either in adequate or contradict with other policies from different ministries. It is essential to have clear policies that illuminate the whole tourism industry including new forms as they manifest themselves in many names and ignore the complexity surrounding the concept’ It is recommended that policies should be clear and facilitated by good governance. The government through its responsible bodies needs to review the existing policies and encourage participation of inbound tourists.

Keywords: Community based tourism, Government, Tourist destination hosts, Policies, Legal framework

INTRODUCTION

Sustainable tourism as an umbrella concept embraces social integrity and economic, natural, cultural and financial resources on an equitable basis that contribute to unique touristic experiences. According to Bassi [1], identifiable characteristic of a sustainable tourism can be acknowledged if it is community oriented (all stakeholders are directed towards community development) and goal oriented (a portfolio of realistic targets centered on the equitable distribution of benefits.), comprehensive (with social, culture, economic, political and environmental implications), iterative and dynamic (being readily responsive to environmental changes), integrative and renewable to incorporate principles that take into account the needs of future generations. it is sustainable when its development includes the participation of local population, with reasonable economic returns and mutual respect to all peoples. Although the profit motive is a major apprehension in income generating actions, historical levels of profits are not always compatible with sustainability, it can be used by individuals to give green credentials for personal gains Adi [2]. The trade-off between profits and sustainability leads to new challenges related to the priorities accorded to social benefits with relatively little focus on economic workability. This sanction the importance of having solid and autonomous macro policies and other protectorates of the governance. In developing countries, the needs for foreign currencies are implemented at the expense of local communities at popular tourist destinations.

The development of new forms of tourism (non-consumptive) work on the premise that, in order for nature conservation efforts to succeed, local communities at the destination has to be active participants and beneficiaries of tourism activities. Some countries are glimpsing the benefits in terms of jobs to outstrip traditional models centered on tourism resource consumption with principles of rationalization. New forms of tourism are however an area of conflict among residents and the governments which create a gap between theoretical rhetoric and the realities at local communities’ level [3]. Governments often perceive tourism as a major industry that can boost the ailing economy. Despite tourism potentials as a poverty alleviation tool, its success depends on the need to onslaught on poverty using the weapon of tourism. In Tanzania tourism is shown is the fastest growing sector, its contribution to the national coffers has been rising and became a model of economic reform process and one of the main sources of diversification of economic activities by channeling investments directly to local communities where poverty is concentrated [4]. The sector is however faced by numerous obstacles including contradictory policies, land uses conflicts, and weak local institutions [5].

GOVERNMENT POLICIES

The term policy can be defined as a predetermined course of action established to guide the performance of work towards accepted objectives or serve as specific guidelines for people as they make decisions, philosophies and values as to how people should be managed. They derive principles upon which people expected to act and reflect the decisions made by various agencies and commissions, parliamentary outcomes, legislation and court judgements [6]. Policies reflect the formal rules, informal constraints and the enforcement characteristics of institutions and other organizations Industrial policy in tourism is prone to political caption and corruption levelled against other areas and does not prima-farcie provide a clear case concerning the new form of tourism.

The basic role of government is to set minimum standards of business morality and aid to enforce the rules. As stated by Vieira [7], the government behavior influences industrial performance, provide security and legal services with power grounded in perception on the industry for social and economic gains through multiplier effects. Some regulations are often aimed at larger companies while legislated support for local communities’ arts does not exist. The government has power which lies in its political and perception about the industry to provide sanctions, incentives, essential services, laws and overall land management and can take in tourism as a major industry to boost ailing economies [8]. Since tourism depends on quality of the environment and political stability, governments are having a significant role to play as the managers of landscape, nature, villages, protected areas and the suppliers of public utilities. As a result, countries with foreign exchange deficit can be rectified by the income from tourism [9]. Many macro tourism related policies in developing countries gloss over the socio-economics inequalities, as a result, the benefits accrued to destinations hosts have been difficult to achieve.

METHODOLOGY

A cross sectional survey design was adopted survey due to its ability to explain the prevailing conditions as perceived by the respondents, the studies are carried out once at a particular point in time and is not repetitive in nature [10]. The Northern Circuit is the main tourist destination in Tanzania with availability of respondents who could provide relevant information as per the study objectives. Information was gathered from 210 respondents using a 5-point Likert scale from the list of 22 statements (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) which were assessed using mean scores, standard deviations and reliability tests and the correlation coefficients of the critical constructs were analyzed.

Findings

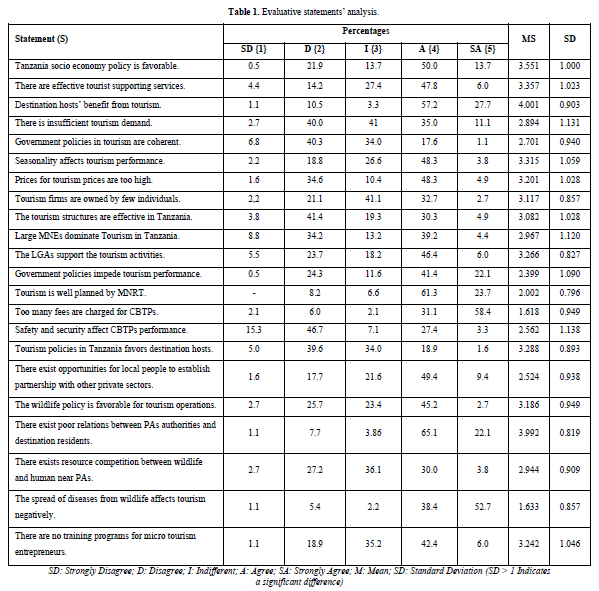

22 statements (S) from the questionnaire were presented for analysis in Table 1.

As seen in the Table 1, S3. ‘Destination hosts’ benefit from tourism operations in the Northern circuit tourist destination” was rated highest with a mean score (MS) of 4.001 and standard deviation (SD) of 0.908, followed by S 19 that “there exist poor relations between PAs authorities and CBT” with a MS of 3.992 and SD 0.819. S 14, that “too many fees are charged for CBT in Arusha” was rated the lowest, with a MS of 1.618 and SD of 0.949. Similarly, S7 - that “the CBTPs products prices are too high” was dropped due to its unreliability. Since correlation coefficients revealed the relationship and magnitude of relationships, it was important to analyze the correlation coefficients of the critical constructs as elaborated in Table 2.

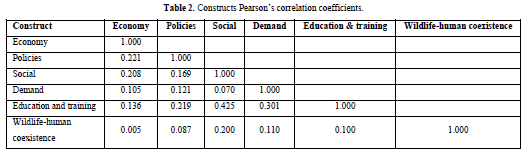

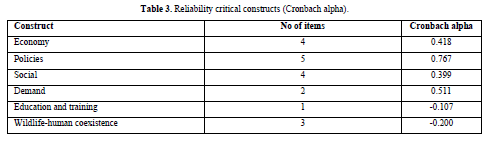

The Pearson’s correlation coefficient varies from a range of +1 to -1 i.e. a relationship existed and the absence of the relationship is expressed by a coefficient which is approximately zero. That is, the correlation coefficient of 0.121, for example, expressed that there is a relationship between Construct 4 (demand) and Construct 2 (policies). Equally, Cronbach’s alpha has a theoretical relation with factor analysis expressed as a function of the parameters of the hierarchical analyses which allows for a general factor that is common to all of the items of a measure. Based on 22 statements within the responses, reliability analysis was carried out. The results of reliability tested were presented in Table 3.

A ‘construct’ is an idea specifically produced for a given research or theory-building purpose. To test the reliability of identified critical construct, Table Large MNEs dominate Tourism in Tanzania 2 shows that the reliability coefficients (Cronbach alpha) are higher than 0.39 except for construct 5 (education & training) and construct 6 (wildlife conflicts). The Cronbach alpha is significant for Construct 2 (government policies) with a Cronbach alpha of 0.767. S7 was dropped due to its unreliability nature (eigenvalue < 1.00).

ECONOMIC POLICIES

The statements relating to economy include;

S1: Tanzania socio-economy is favorable for new forms of tourism development.

S3: ‘Destination hosts’ benefit from tourism operations in Tanzania”.

S8: New forms of tourism are owned by few individuals.

S10: Large MNEs dominate Tourism in Tanzania.

Economic factors have a low Cronbach alpha of 0.418 denoting the economy has no significant influence on new forms of tourism development (not ≥ 0.7). The growth or decline in GNP, interest rates, inflation and exchange rates present both opportunities and threats but the insight is the market size as essential determinant and provide more diversified services for higher standard of living for local residents.

The government represents people who have basic powers to influence the policy implementation, the emphasis on public - private partnership in which the latter identifies opportunities and constraints and the former generate policy initiative to build value chains for smooth performance. As a public interest protector, policy decisions should reflect a desire and interests of all stakeholders rather than the sectional interests of the industry, stimulate tourism through financial incentives, research, development projects, own and operate owned business though entrepreneurial climate is changing with less government intervention towards public-private partnership, revalorize the concept of capital by subsidizing part of invested costs into social costs [7]. There are many cases where governments have focused on immediate and rapid actions for short run revenue earnings at the expense of local communities.

‘While in Kenya for example, the scarce water which was once used by the Samburu communities (close to Shaba Reserve) was diverted to fill the swimming pool of the Sarova Hotel [11], in South Africa, tourism effort is often directed towards large multinational tourism operators and exclude domestic tourism initiatives which led to limited employment opportunities in famous destinations like Kruger National Park and Victoria Waterfront.

Similarly, in Israel, national tourism development plans have been drawn up where the government identifies which tourism sectors will be developed and the appropriate growth rate and provides the capital required for that expansion, in India, several states have created tourism development corporations for the purpose of encouraging tourism development and investment at local level [12] and in Nepal, the Chhetri people were moved from their lands to give way for Lake Rara National Park’.

Most respondents failed to balance between economic and cultural motives. Whilst motivations other than profit making are compatible with the notion of sustainability, economic benefits should be considered in line with cultural workability. Many ventures are found to be possessed and benefited by a few individuals with few benefits to local communities. Nevertheless, some youths and women perform cultural dances and sell crafts, these activities provide a smaller supplement to participants few employees enter into lower wages leading to doubts whether new forms of tourism practices are economically feasible [4]. Transparency and good communication are qualifications that do not match the practice, though income from new forms of tourism provide an array of communal and individual benefits.

TOURISM POLICIES

Constructs relating to policies were captured to include;

S5: Government policies on new forms of tourism are coherent.

S11: The LGAs support the new forms of tourism in Tanzania.

S12: Sectoral policies impede new forms of tourism performance in Tanzania.

S13: New forms of tourism is planned by the Ministry of Tourism.

S9: The tourism structures are effective in Tanzania.

S14: Too many fees are charged for new forms of tourism.

S16: Tourism policies in Tanzania favor new forms of tourism activities.

Government policies were found to have a high Cronbach alpha of = 0.767, and correlation coefficient of 0.221 at p = 0.01, implying the existing policies influence the performance of new forms of tourism. The relationship between new forms of tourism, policies and legal framework is a multifaceted construct. 58% indicated the government to focus too much on affirmative actions for economic gains, 56% showed lack of positive implementation by the government, 36% indicated the government lacks the ability to enforce local regulations. Thus, good governance at different levels matter for increased accountability and the practices at the village level differs from stipulations within various policies.

The National Tourism Development Policy (1991) provide overall objectives and strategies for sustainable tourism development in Tanzania, though do not indicate specific efforts needed to empower local communities’ involvement in tourism. Entrepreneurs often are willing to accept personal or financial risk to pursue opportunities as opposed to "political entrepreneurs" who uses political influences to gain income through subsidies, protectionism, government-granted monopoly or contract. Local people operate without special favors from the government but depend on fair policies and a favorable legal framework. However, the policy is too hold and may not carte the needs of new forms of tourism.

WILDLIFE POLICIES

Wildlife Policy (1998) broadened the scope of interpretation in order to guide the private sector to enable local people’s participation in new form of tourism. Wildlife Conservation Act (WCA 1974) provides few opportunities for local communities though it is centered on game-controlled areas (GCAs) as they tend to overlap demarcated village lands by allowing people to generate income from new form of tourism and provide the creation of wildlife management areas (WMA 2002). WMAs allow local communities to access wildlife resources outside protected areas (PAs). Tourism investors are thus increasingly choosing this model where a portion of revenue from new forms of tourism goes to local communities in exchange for the use of their land.

SMEs DEVELOPMENT POLICY

The concept of ‘development’ embraces wider concerns of life and desirable changes depending on the objectives advocated [13]. Since micro and small tourism enterprises fall under SMEs development policies, they have been facing a number of problems due to persistent culture that has not recognized the value of entrepreneurial initiative in improving the lives of local people”. Costly legal regulatory and administrative environment also push SMEs to greater disadvantage.

SOCIAL RELATED POLICIES

From Table 1, the statements evaluated relating to social factors includes:

S2: There are effective supporting services and organizations.

S15: Safety and security affect the performance of new forms of tourism.

S17: There exist opportunities for new forms of tourism to establish partnership.

S21: The spread of diseases negatively affects new forms of in Tanzania.

In the context of socially construed factors, the Cronbach alpha of 0.399 with correlation coefficients of 0.169 at p = 0.01, implying a positive correlation between social factors and existing policies. Social forces include societal trends, traditions, values, consumer psychology and society’s expectations of a tourism venture. There is however a plethora of codes of conduct or codes of ethics to guide a socially responsible business which are adopted within a sector or specific geographical area [10]. The nature of the industry requires that members participating in new forms of tourism should adopt a 'can do' attitude in collaboration with development partners if they are to survive and grow.

TOURIST SUPPORT SERVICES AND SAFETY

48% of the clients rated security and safety as low, 33% rated it as high and 19% were indifferent. In terms of security and safety for visitors in local communities, Tanzania is ranked as the safer destination than other countries Africa. The factors that hamper safety and security were found to be beyond the abilities of the owners of new forms of tourism such as petty crimes and the slow actions by responsible authorities (police forces) which impinge credibility and ultimately performance. The recent global terrorism had profound effects on tourism is affected by and attacks that aim at the citizens from most tourists generating countries.

Safety is a principal factor in any destination, it is beyond the abilities of the owners of new forms of tourism. Lack of insurance cover against risk is shown to be one of the reasons given by many respondents. The anti-terror insurance cover is not attractive due to its high cost based on the perceived high risk in the region and tariffs are based on individuals while different destinations and locations have different risk factors. Since local people do not have institutional capabilities, there is a need for development partners to support new forms of tourism. Formal private sector possesses sound business acumen and drive, NGOs can provide a range of services including capacity building, arbitration for conflict resolution, access to capital and facilitation of negotiation between local communities.

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEMAND, INTEGRATED EFFORTS AND PRICES

Constructs relating to demand were summarized in the following statements:

S6: Seasonality affects new form of tourism performance.

S4: Insufficient demand for new form’s services affects their performance.

The correlation coefficient of 0.121 between demand and policies indicates that the reliability critical constructs (Cronbach alpha) for demand was 0.511, implying that there exists a positive correlation between the two constructs. Tourism demand is a two-pronged approach, i.e., both the government and the service providers have a role to play to create demand. Based on the nature of this study, local communities need the effective role of the government if they are to perform. The traditional approaches to new forms of tourism have looked at the issues of supply and demand largely from the demand side, which has led to the construction of new forms of tourism based on the regime of cultures consumed by the tourists and packed by the industry.

Changes in tourists’ expectations and values are becoming the main drivers of the pace and direction of tourism development [14]. In the leisure market, tourists are becoming less satisfied with traditional holiday packages and traditional or mass tourism and are being replaced by new forms of tourism. As argued by Clarke [15], new tourists have more experience, more quality conscious, environmentally aware, more independent and harder to satisfy using traditional tourism commodities. The quality and value for money are thus vital for new forms of tourism performance.

Performance of new forms of tourism enterprise depends on integrated efforts, support of government policies, smooth operations from different institutions, economic diplomacy commitment and international cooperation. Although Tanzania has acquired membership of various international organizations, such as the World Tourism Organization (WTO), the Regional Tourism Organization of Southern Africa (RETOSA), the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), the African Travel Association (ATA), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), the East African Community (EAC) and formerly a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the present bilateral and multilateral relations have not been fully capitalized on development of new forms of tourism.

The rise of globalization and the information society presents a new set of challenges at the interface between technological innovation and growth of new forms of tourism. A growing body of evidence indicates that a more holistic and innovative strategy leads to higher levels of compliance. 55% of the responses indicated that taxes and other fees paid are high, 35% rated as fair and 10% rated as low implying service prices from different bodies of the government are high and unprofitable for the growth of new forms. Consequently, poor infrastructures, increasing fuel prices, the informal contributions charged by service providers and seasonality have negative impacts on success and growth. The products pricing system was generally found to be unrealistic and it was difficult to ascertain whether or not the contribution of publicity and its associated costs would have any impact on the inflow of tourists who are searching for authentic experience rom new mode of tourism.

Education and Training

The construct related to education and training was found in statement 22 as stated below;

S22: There are no training opportunities for owners of initiatives if new forms.

The correlation coefficient between education/training and policies is 0.219 at p = 0.01, education and training had a Cronbach alpha of - 0.107, implying there exists positive correlation between the constructs, though the reliability test indicate the opposite direction. Impliedly, most owners of new forms of tourism lack adequate professional education, periodic training and skills to supplement their indigenous knowledge and other abilities. New form of tourism is seen as a means to achieve learning, training and maintaining on going contacts with clients for transmitting cultural knowledge between generations and boost hope and self-esteem accorded by tourism.

Training emanates ‘investing in people to promote productive work-places by addressing human dimension and competitiveness with a focus on the level of understanding of the local people. Tanzania is endowed with a rich natural resource base but the challenge lies in the ability to transform efficiently into goods and services that can be availed to the market at competitive prices” [16]. The owners of new forms of tourism have lower demand for business development services, research and development (R&D), counselling and do not appreciate the importance of education due to cost considerations and lack of knowledge in regard to benefits.

WILDLIFE-HUMAN COEXISTENCE

The statements relating to wildlife conflicts as seen in Table 1 include:

S18: The wildlife policy is favorable for new forms of tourism operations.

S19: There exist poor relations between PAs and new forms of tourism.

S20: There exists resource competition between wildlife & human near PAs.

The coefficient correlation between wildlife-human coexistence to be 0.087 at p = 0.01 and the reliability test showed Cronbach alpha of - 0.200 implying existence of negative effects between the construct. These findings are similar to those of the knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) survey by Munishi [17] in the villages around Tarangire and Manyara National Parks concerning the benefits and challenges arising from human and wildlife coexistence in the area. Villages bordering national park were suffering due to wildlife migration within game-controlled areas (GCAs). The conflicts emanate from the risk of predators, sharing of scarce resources, transmission of diseases from wildlife to human beings which amplifies poverty among local communities.

Wildlife-human conflicts generally emanate from the government laws that essentially define for the society as a whole, which actions are permissible and which are not and establishes the minimum standards of behavior and conduct. New forms of tourism initiatives often encounter legal and conflicting interests with the PAs and LGAs on balancing between wildlife conservation and human economic development [18]. In South Africa, most national parks are fenced but some are being removed as part of the initiative to link the PAs across national boundaries leading to intensified conflicts between wildlife and human with inability of the government to compensate the damages [19]. Although the community based natural resources management (CBNRM) gives rights to local communities over wildlife and tourism resources, but many of them are failing due to a wide range of factors. In Zimbabwe for 9, more often the wildlife roam outside the PAs in adjacent villages and cause nuisance to the people outside the PAs.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Tanzania has wealth of natural and cultural heritage to provide unique experiences to tourists, though most of the guiding policies are either in adequate or contradict with other policies from different ministries. It is essential to have clear policies that illuminate the whole tourism industry including new forms of tourism as subsets of sustainable tourism as they tend to manifest themselves in many names and ignore the complexity surrounding the concept through identification of emerging preferences and product possibilities. It is recommended that policies should be clear and facilitated by good governance to sustain resources, and partnership structures. The government through its responsible bodies needs to review current the existing policies and focus encourage inbound tourists. Further studies need to be conducted on some conflicting policies between new forms of tourism and wildlife conservation.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :